Created in his own image

Book Review:

Yuval Noah Harari, "Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow", Vintage, 2017.

Previously, we saw how Homo sapiens was able to conquer the world due to a handful of key events:

- The Cognitive Revolution and emergence of fictive language about 70,000 years ago

- The extinction of American and Australian megafauna as well as other human species (like Neanderthals and Homo floresiensis) by 13,000 years before the present

- The Agricultural Revolution and establishment of permanent settlements, kingdoms, scripts, money, and polytheistic religions between 5,000 and 12,000 years ago

- Empires, coinage, and monotheistic religions between 2,000 and 4,250 years ago

- The Scientific Revolution, Industrial Revolution, European colonialism, capitalism, and further extinction of plants and animals between 200 and 500 years ago

The second book, Homo Deus, picks up right where Sapiens left off. Well, it actually repeats much of what was discussed in Chapter 20 of Sapiens, namely that we might one day use biological engineering, cyborg engineering, and the engineering of non-organic beings to upgrade humans into "gods". Here, the author does not mean God in the sense of an omnipotent or metaphysical father, but in the sense of ancient Greek and Hindu gods and goddesses who were neither omnipotent nor perfect, yet nevertheless had specific super-abilities (such as escaping death). This pursuit of divinity will be one of the three projects of the 21st-century, according to Harari. The other two are (a) the struggle to defeat aging and death, and (b) the search for the key to everlasting happiness.

Why so? Because as was also mentioned in Sapiens, we have made a tremendous amount of progress in the last couple of decades in terms of reducing disease, violence, and famine. Today, most people are unlikely to die from hunger, child mortality is at an all-time low, and war kills just 1/5 as many people as suicide. Since these issues are not likely to remain on top of the human agenda for much longer, there will be a new human agenda to take their place. After all, one of the lessons that Harari extracts from history is that humans "are rarely satisfied with what they already have".

In contrast to Sapiens, which has 20 chapters spread across four parts, Homo Deus has 11 chapters across three parts. This is not because the book is shorter (it is just as long), but because the chapters are longer. Therefore, I will proceed to summarize the book chapter-by-chapter.

***

What is our relationship with other animals, and what makes us special?

"You want to know how super-intelligent cyborgs might treat ordinary flesh-and-blood humans? Better start by investigating how humans treat their less intelligent animal cousins." (p. 77)Who are we really? Well, unlike any other species, we have the power to change the global ecology on par with tectonic plate movements, ice ages, and perhaps even asteroids. Hence, in the author's words, we have "rewritten the rules of the game", and we are beginning to replace natural selection with intelligent design. Since the Agricultural Revolution, humans started to believe in their own distinctiveness, and consequently that domesticated farm animals are inferior -- a belief that has caused massive amounts of animal suffering. However, like pigs and chickens, humans are algorithms with emotional needs but without eternal souls; there is no "magic spark" besides our higher intelligence and greater power.

Just because humans are powerful, it does not necessarily follow that human lives are morally more valuable than the lives of pigs. Monotheistic religions like Christianity have traditionally argued that humans uniquely have souls, and even today some folks reject Darwin's theory of evolution on the basis that evolution contradicts their cherished belief in the soul. Harari notes that under the framework of evolution, an organism does not have some indivisible essence, but is made from a combination of smaller and simpler parts developed over millions of years. But even if we do not accept the notion of an immutable soul, many people argue that it is consciousness that justifies human superiority. While scientists do not yet have a good understanding of consciousness, one theory is that consciousness is a by-product of the electrochemical firing of complex neural networks as they process data. And the electrochemical "signatures" of consciousness (i.e. the activation of certain brain areas), detectable using fMRI, have indeed been identified in monkeys and mice. So if we are not special in those ways, how come we are able to dominate other animals? The answer, according to Harari, is that Homo sapiens is the only species capable of cooperating flexibly in large numbers. This cooperation is based on the intersubjective reality of imagined orders, such as God, money, and nations. We study these intersubjective entities not through the lens of biology, but through the humanities; as the author writes: "Meaning is created when many people weave together a common network of stories. [...] To study history means to watch the spinning and unravelling of these webs, and to realise that what seems to people in one age the most important thing in life becomes utterly meaningless to their descendants" (pp. 170-171). This reinforces what I said in my previous post regarding the power of imagination.

How does the humanist creed create meaning in our world?

"For 300 years the world has been dominated by humanism, which sanctifies the life, happiness and power of Homo sapiens. The attempt to gain immortality, bliss and divinity merely takes the long-standing humanist ideals to their logical conclusion." (p. 75)How did humanism become the dominant world religion? As we saw, humans are unique when it comes to intersubjective stories about money, gods, nations, and corporations. These stories, with the help of writing, allowed societies to organize themselves bureaucratically, which facilitated mass cooperation but also meant that reality was sometimes pushed aside in favor of what was written down by the authorities. Rulers are able to reshape reality with the stroke of a pen, because people are forced to take written records seriously (otherwise they tend not to get very far in life). Sometimes this leads to suffering, for example when belief in national or religious myths causes war. But fictions are necessary for complex societies to function, to play football, and to enjoy the benefits of markets and courts. We just need to keep in mind that stories are tools and are separate from reality.

In contrast to holy scriptures, modern science actually can cure infections... yet according to Harari, myths "continue to dominate humankind, and science only makes these myths stronger" (p. 209). This is because science tends to blur the boundary between the objective reality and subjective reality by empowering people to control the world in line with their wishes. Thus, science and religion seem to be an "odd couple" in the author's words. As in Sapiens, Harari still defines religion as "any all-encompassing story that confers superhuman legitimacy on human laws, norms and values" (p. 211) without necessarily being about a superstitious belief in supernatural gods. Therefore, communism and Nazism and liberalism are all religions. While science is able to answer factual questions, it cannot tell us how we ought to behave without the guidance of religions (although it can challenge the practical guidelines of religion when those are based on factual assumptions). And here we can finally discuss the historical deal between science and the religion of humanism, whereby humanism is interested in how to order the social structure, and science helps to implement the dogma by giving it power.

According to Harari, the deal of modernity is that humans give up meaning in exchange for power. In the premodern era, people believed that the "cosmic plan" that had power over them gave their lives meaning, whereas modern cultures do not believe that life has an inherent meaning -- and therefore, we are free to do as we desire. With enough research and invention, we may obtain the power of near-omnipotence. In the modern age, people started having trust in the future, which fueled the expansion of credit in the economy and the reinvestment of profits. Today we seem obsessed with economic growth. Yet free-market capitalism makes ethical judgments (e.g. that growth is more important than family bonds) and as such qualifies as a religion, in Harari's view. And science has been an ally to capitalism by finding new sources of raw materials and energy so that the economy can keep growing. If this trend continues, our biggest challenge is unlikely to be resource scarcity, but rather ecological collapse (such as from climate change), or more stressful lives for individuals. So far, it seems like modernity has kept its promise of giving us unprecedented power. As the author notes: "For thousands of years priests, rabbis and muftis explained that humans cannot control famine, plague and war by their own efforts. Then along came the bankers, investors and industrialists, and within 200 years managed to do exactly that" (p. 256). But how did humans cope with having to give up meaning? This is where humanism comes in.

Humanism says that we create meaning by drawing from our inner experiences, and therefore that we ourselves can determine what is good and evil, what is beautiful and ugly, and how to think and behave. God is no longer the supreme source of meaning and authority. Humanism has influenced politics ("the voter knows best"), aesthetics ("beauty is in the eye of the beholder"), economic production ("the customer is always right"), and education ("think for yourself"). Humanism even provides a formula for how we can find answers to ethical questions: one must collect inner experiences and observe them with the utmost sensitivity. Knowledge = Experiences * Sensitivity. One should pay attention to one's sensations, emotions, and thoughts, and allow these to influence oneself. Life is thus a gradual process of inner change. This modern formula has changed our popular culture as well as narratives about war -- no longer do people focus on the heroic deeds of brave warrior-kings or the chess moves of great generals; rather, modern art and literature focus on the feelings, experiences and opinions of ordinary soldiers. But for much of the 20th-century, humanism was not a single coherent world-view: it was split into three conflicting sects. The liberal humanists (today the orthodoxy) believe that every individual human being is unique and should be given maximum freedom -- we should equally cherish all experiences. In contrast, the socialist humanists (e.g. the Soviet Union) maintained that humans could only escape misery by looking not inwards but at the experiences of other humans, and changing the prevailing socio-economic system via collective institutions. The evolutionary humanists (e.g. Nazi Germany) celebrated conflict as a means of selecting the strongest and fittest humans, who would spearhead human progress. Yet in the 21st-century, liberalism is still dominant. One reason why liberalism won (and why there is no real alternative to it) is that it understands and keeps up-to-date with technological breakthroughs, like artificial intelligence and biotechnology. Traditional religions such as Christianity or Islam do not have anything creative to say about computers, the Internet, nanotechnology, or the human genome. However, even the liberal package of individualism, human rights, democracy and free markets is in danger of being left behind by new post-human technologies.

Might we lose control over the future?

"People are usually afraid of change because they fear the unknown. But the single greatest constant of history is that everything changes." (p. 78)Why may attempts to fulfill the humanist dream cause its downfall? Metaphorically-speaking, there is a time bomb in the labs of science, because the discoveries of science are increasingly undermining the factual beliefs that underlie liberal humanism. Harari focuses on the liberal values of liberty and individualism, and asserts that these values do not match the scientific reality that (a) there is no free will, as our decisions can be explained in terms of biochemical reactions, and (b) there is no single true self, as we are divisible into conflicting "voices" (for example the left hemisphere vs. right hemisphere, or Kahneman's experiencing self vs. the narrating self). Additionally, the theory of evolution doesn't leave much room for us to choose our own desires. Now, I have already remarked in my review of Sapiens that I disagree with the author's stance on the meaning of life, and I would like to repeat that here because in Homo Deus he writes: "Medieval crusaders believed that God and heaven provided their lives with meaning; modern liberals believe that individual free choices provide life with meaning. They are all equally delusional" (p. 354). This seems like a case of the fallacy of gray. But to be charitable to Harari, his key idea that liberalism is threatened by concrete technologies may still be valid; so what are these practical developments?

Robots and computers are quickly catching up to humans and may soon surpass us in intelligence. However, since they are unlikely to be conscious, there will be a decoupling between intelligence and consciousness. Unfortunately for humans, the economic and military systems need intelligent agents and not necessarily subjective experiences. Drivers, factory workers, bank tellers, travel agents, stock traders, lawyers, teachers and doctors all may eventually be replaced by sophisticated algorithms, which unlike humans will never be tired, hungry or sick. Thus, most humans may become useless to the point where wealth and power will be concentrated like never before in the hands of an "algorithmic upper class", as the author calls it. But even if humans do not become useless, the system may cease to find value in unique individuals because the authority and freedom of the individual will be replaced by the decisions of external algorithms that know people better than they know themselves. According to Harari, liberal individualism maintains that nobody knows who you really are and what you really want better than you do -- however, at some point in the 21st-century, your life will be run by various technologies based on biometric, genetic, and online (e.g. search and social media) data. After all, once the system actually does know you better, why would you trust yourself to get an important decision right? Finally, the third threat to liberal humanism is the creation of a new class of elite, upgraded "superhumans". If most humans are not upgraded, this will cause humankind to be split into biological castes, whereby the elites will excel physically, emotionally and intellectually, and have fundamentally different experiences. These superhumans may not treat the rest of us according to the liberal idea that all individuals have equal value.

If indeed liberalism does collapse, there are two types of religions that might replace it: techno-humanism, and data religion. Techno-humanism proposes that while Homo sapiens may become irrelevant in the future, the essential humanist values can be preserved by upgrading our physical and mental abilities to match those of non-conscious algorithms. This upgrade would give us new conscious experiences and mental states, but as Harari notes: "We are akin to the inhabitants of a small isolated island who have just invented the first boat, and are about to set sail without a map or even a destination" (p. 411). The spectrum of all possible mental states is arguably vastly larger than that experienced by the Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) university students who represent most of the human subjects so far studied by psychologists. It is larger still than the spectrum experienced by non-human animals like bats or whales. Therefore, the techno-humanist project may inadvertently downgrade humans if the narrow interests of the military and economic systems, combined with our ignorance of the mental spectrum, lead us to engineer humans who are highly-efficient cogs yet nevertheless can "hardly pay attention, dream or doubt". Furthermore, techno-humanism sanctifies the human will, but the author asks: what happens when we are able to control and redesign the will, and choose our desires? There is a different religion that is fine with getting rid of humanlike desires altogether.

The data religion, or Dataism, says that the universe including life itself consists of the flow of information, and that value derives from data processing. Dataism has its roots in both biology and computer science -- organisms are seen as biochemical algorithms, yet since humans can no longer cope with today's immense flows of data, we are better off entrusting the work of data processing to electronic algorithms. Dataism provides a kind of "theory of everything", whereby everything from musical compositions to the economy, the political structure, and the influenza virus can be explained in terms of data-processing patterns or systems. Capitalism and democracy are examples of distributed processing, while communism and dictatorships are examples of centralized processing. The reason why democracy and the free market "won" was because they improved the global data-processing system; however, Harari argues that in the future, we may need new and more efficient structures. This relates to an interesting observation Harari makes about our current political conditions: "Precisely because technology is now moving so fast, and parliaments and dictators alike are overwhelmed by data they cannot process quickly enough, present-day politicians are thinking on a far smaller scale than their predecessors a century ago. Consequently, in the early twenty-first century politics is bereft of grand visions" (p. 438). To quickly recap history: the cognitive revolution 70,000 years ago increased the number and cultural variety of Homo sapiens as we spread across the globe; the agricultural revolution further increased the number of human processors; the invention of writing and money 5,000 years ago then enabled the connection and cooperation of humans across cities, kingdoms and empires; and finally the scientific revolution about 500 years ago helped information flow even more freely. Thus, at each stage the human species as a whole became more efficient at processing data. And the next stage, according to Harari, may be the Internet-of-All-Things. The data religion requires us to maximize data flow by connecting every thing (including humans, cars, chickens, and refrigerators) to the system, the Internet-of-All-Things, because freedom of information is the greatest good of all. Of course, this would conflict with individual humans' right to private ownership -- and the Dataist response is that merging with the dataflow will make you part of something much bigger than yourself, and that meaning lies not within the self but in sharing data. Once authority shifts to the algorithms, and "once we humans lose our functional importance to the network, we will discover that we are not the apex of creation after all. [...] Looking back, humanity will turn out to have been just a ripple within the cosmic dataflow" (p. 460).

The book ends with a disclaimer that these scenarios are not guaranteed to happen, and that the primary purpose of Homo Deus was to broaden our horizons of what is possible. Nonetheless, we should ask ourselves the following questions: "Are organisms really just algorithms, and is life really just data processing? What's more valuable -- intelligence or consciousness? What will happen to society, politics and daily life when non-conscious but highly intelligent algorithms know us better than we know ourselves?"

***

Having read Homo Deus right after finishing Sapiens, it was natural for me to judge this book as a sequel. From that perspective, Homo Deus was somewhat underwhelming because much of its content was a reiteration of what the author discussed in Sapiens. The ideas that humans were able to dominate the world due to large-scale cooperation, that this cooperation was facilitated by the cognitive, agricultural and scientific revolutions, that "imagined orders" like religions, money and nations played an especially important role, and even that humanist religions come in three flavors (i.e. liberal, socialist and evolutionary humanism) are all ideas that feature prominently in both books. Additionally, Yuval Noah Harari uses both books to denounce industrial animal farming and to subtly compliment Vipassana meditation. He repeats the idea that life is meaningless -- see my initial response here. For all these similarities, I doubt whether anyone really needs to read both books; perhaps Homo Deus by itself would suffice, because it is essentially a condensed version of Sapiens with some extra speculation about the future tacked on.

That said, the extra speculation about the future is quite interesting, and it can be found mostly in Part III of the book. The author argues that the liberal values of individualism and free will are under philosophical threat by recent findings in science, but in my opinion this is the weakest part of his thesis. The stronger part is the idea that future technological progress could disenfranchise the majority of humans on the planet by diverting economic and political power to either (i) a system of super-intelligent non-organic algorithms; or (ii) a class of elite superhumans. Apart from these concerns, we may also be concerned about the way that more and more of our decisions are being made for us by technologies. If these possibilities are realized, the socio-cultural implications may include new religions, such as techno-humanism (placing value in upgraded humans with new kinds of mental experiences) or Dataism (placing value in data processing and sharing, apart from any consciousness). In either scenario, Homo sapiens may no longer be recognizable.

Thus, the core lesson of Homo Deus is that our pursuit of health, happiness and power may inadvertently lead to a world wherein humanist projects are no longer relevant. However, this point must be taken in the context of the other lesson of Homo Deus, which Harari explains in a section titled 'A Brief History of Lawns':

"Historians study the past not in order to repeat it, but in order to be liberated from it. [...] By observing the accidental chain of events that led us here, we realise how our very thoughts and dreams took shape -- and we can begin to think and dream differently. [...] Having read this short history of the lawn, when you now come to plan your dream house you might think twice about having a lawn in the front yard. You are of course still free to do it. But you are also free to shake off the cultural cargo bequeathed to you by European dukes, capitalist moguls and the Simpsons -- and imagine for yourself a Japanese rock garden, or some altogether new creation." (pp. 68-74)In many ways this echoes the sentiment of Chapter 13 in Sapiens, which states that the study of history is meant to broaden our horizons. Again, there is an overlap between the two books, so to the extent that Homo Deus is interpreted as a sequel, it falls short of expectations for much "fresh" new content.

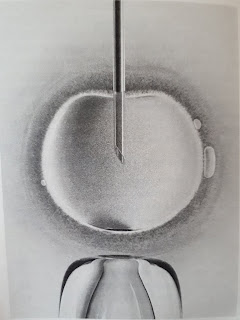

However, when interpreted as a standalone book, Homo Deus is excellent (and perhaps even more so than Sapiens thanks to its more flowing style). Its strengths include accessibility, engagement, and the addition of illustrations to break up the wall of text. Readers who only read Homo Deus will still leave with a good big-picture understanding of human history, as well as an appreciation for how much agency we have for choosing our future. History shows us the power of ideas, values and norms, and so encourages us to think about how we want the history of tomorrow to be written.

I gave this book 5/5 on Goodreads because I would recommend it to anyone. In the future I might write a post explaining in more detail why I'm not fully convinced by the author's interpretation of the meaning of life, and/or how a superintelligent algorithm need not pose an inherent threat to human values (hint: something something CEV).

Comments

Post a Comment