Of Animals and Machines

Book Review:

George Akerlof and Robert Shiller, "Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism", Princeton University Press, 2009.

~and~

Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, "The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies", W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

This is the first time on my blog that I am reviewing two books together, but I thought it made sense in this case because the books are complementary: both are about economics, yet they take different perspectives. Animal Spirits by Akerlof and Shiller is essentially a vision of "behavioral macroeconomics", criticizing the mainstream standard story about the economy as incomplete and offering a theory that includes human psychology. The Second Machine Age by Brynjolfsson and McAfee applies the principles of economics to the issue of technological change in the 21st century and argues that the digital transformation will bring about massive benefits but also disruption, on a level comparable to the Industrial Revolution.

At first glance, these two books appear to be talking about very different things; however, they both point toward blind spots in our perception of economic trends and circumstances -- the neglect of psychological forces in the case of Animal Spirits, and the neglect of the "exponential, digital, and combinatorial nature of progress with digital technologies" in the case of The Second Machine Age. While animals and machines may sometimes be regarded as polar opposites, they are both necessary for understanding the world around us. In particular, my interpretation of Animal Spirits is that human psychology operates on a relatively short-term timescale (i.e. days, months, or a couple of years) whereas technological changes like The Second Machine Age have more predictive power on a relatively longer timescale (i.e. years to decades). I base this claim on the fact that Akerlof and Shiller mainly seek to explain economic phenomena such as recessions, unemployment, asset prices, interest rates and savings, which are typically analyzed using a different time frame than are the technological innovations like Artificial Intelligence (AI) that Brynjolfsson and McAfee want to examine.

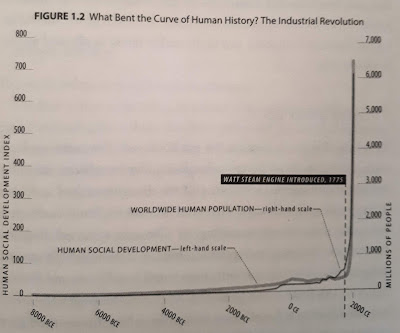

To clarify what I mean, consider that the Great Depression in the United States lasted from 1929 to around 1937 or 1938, no more than a decade. And when we talk about the effects of economic policies on inflation or the unemployment rate or GDP or whatever, we rarely presume that these consequences (or even the policies themselves) will be permanent. On the other hand, new technologies -- if widely adopted -- tend to stick around for quite a while, and may have lasting effects (e.g. the automobile has replaced the horse as the popular means of transport). As a particularly striking example, I want to highlight the steam engine, which according to Brynjolfsson and McAfee was the most important technology of the Industrial Revolution in 1775, and explains this chart:

As you can see, the curve shot upwards after 1775, tracking both the global population as well as the "Human Social Development Index". The latter metric was devised by the anthropologist Ian Morris, who defines our ability to master our physical and intellectual environment to get things done, in terms of four factors: energy capture, organization (i.e. city size), war-making capacity, and information technology. The Industrial Revolution (referred to by Brynjolfsson and McAfee as the "first machine age") transformed these factors more than did the domestication of animals, farming, the development of empires, religion, writing, or democracy.

This graph reminded me of an article written by Luke Muehlhauser on his blog, titled "Three wild speculations from amateur quantitative macrohistory". In the article, Muehlhauser uses six measures to plot the following graph:

He thus summarizes human history: "Everything was awful for a very long time, and then the industrial revolution happened."

To return to the book, the "second machine age" is upon us -- at least according to Brynjolfsson and McAfee -- and will involve computers and other digital developments which will greatly amplify our mental power. The authors offer three broad conclusions: i) we are seeing rapid progress in hardware, software and networks; ii) these digital technologies will bring about beneficial transformations; and iii) they will also pose challenges, such as disruption of the labor market.

The conclusions of Animal Spirits, by contrast, are that i) the booms and busts of the business cycle are fueled by people's economic confidence or lack thereof, which has a "multiplier" effect; ii) prices and wages are influenced by considerations of fairness; iii) bad faith, antisocial behavior, and corruption contribute to economic fluctuations -- such as in the predatory behavior that preceded the recessions of 1990, 2001, and 2007; iv) people tend to have money illusion, i.e. they make decisions based on the nominal value of their currency rather than adjusting for inflation; and v) human minds like to think in terms of stories and narratives, which can also inspire high confidence or fear when they become "epidemic". Hence, the five animal spirits that are missing from standard economic models: confidence, fairness, corruption and bad faith, money illusion, and stories.

But Animal Spirits goes beyond an introduction of these forces, and in Part II applies them to eight different economic questions in an attempt to improve upon the standard answers. These questions are: Why do economies fall into depression? Why do central bankers have power over the economy, insofar as they do? Why are there people who can't find a job? Why is there a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment in the long run? Why is saving for the future so arbitrary? Why are financial prices and corporate investments so volatile? Why do real estate markets go through cycles? Why does poverty persist for generations among disadvantaged minorities?

Clearly, anyone who wishes to understand economics should be able to answer these questions. In addition, one should also be able to explain the impact of rapid progress in digital technologies. Therefore these two seemingly different books actually complement each other well.

***

The first part of The Second Machine Age explains why technological progress is accelerating at the moment. As examples of key digital technologies, Brynjolfsson and McAfee mention self-driving cars, natural language processing, IBM's Watson, robotics, and 3D printing. (In the new introduction, they also mention drones, "deep learning", and genomic sequencing.) These innovations have occurred quite recently, which the authors attribute to three key characteristics of the second machine age:

- It is exponential -- Moore's Law says that general computing power (or more precisely, the "amount of integrated circuit computing power you could buy for one dollar") doubles roughly every eighteen months, and this has been the case for over four decades since Gordon Moore made his prediction in 1965. Exponential growth can be hard to grasp intuitively, but in practice it means that the Sony PlayStation 3 sold for $500 only ten years after the ASCI Red supercomputer was built for $55 million in 1996... both computers can reach 1.8 teraflops. Due to the ingenuity of computer scientists and engineers, there are likely to be further doublings.

- It is digital -- Smartphone applications nowadays can send information about traffic jams or road closures to a database in order to calculate the quickest route to a destination, and the more people use the app, the more useful it becomes -- this is called a network effect. This is possible thanks to the conversion of all kinds of information into digital bits, which makes the information a non-rival good with near-zero marginal costs of production. In layman's terms, we can replicate digitized goods perfectly and almost costlessly, and send them across the planet almost instantaneously. This means that the amount of data has exploded.

- It is combinatorial -- Innovation is crucial to productivity growth, and some folks have argued that innovation is slowing down as the low-hanging fruit have been harvested. However, Brynjolfsson and McAfee deny that innovations get "used up"; rather, innovation is about recombining things that already exist. With ICT there are many ways to combine and remix old and recent ideas -- new ways of recombinant innovation. For example, the combination of a fast computer, a bunch of sensors, a lot of map information, and an internal combustion engine can produce autonomous cars. And because possible combinations are multiplicative, the more "building blocks" we have, the more recombinant innovation occurs.

***

Chapter 6 of Animal Spirits talks about the U.S. depression of the 1890s and the Great Depression of the 1930s. The discussion ties together all five forces:

"... a crash of confidence associated with remembered stories of economic failure, including stories of a growth of corruption in the years that preceded the depression; a heightened sense of the unfairness of economic policy; and money illusion in the failure to comprehend the consequences of the drop in consumer prices." (p.59)The 1890s depression was triggered primarily by a bank run in 1893 when people feared that they would lose their savings if the government's gold reserves fell too low (this was before the Federal Reserve Act). The 1930s Great Depression was triggered by the 1929 stock market crash, leading to deflation and low employment. In both cases, workers strongly resisted nominal wage cuts out of a sense of fairness and money illusion, to the point of preferring unemployment. People and businesses lost confidence. Newspapers reported an increase in embezzlement schemes. These factors were linked to stories of previous panics (e.g. 1873 and 1884). And according to Akerlof and Shiller, such events are not confined to the past, because human nature remains as powerful as ever.

The subprime lending crisis of 2007 makes for a good segue into Chapter 7, which discusses central banks as potential heroes in times of recession. The power of central banks comes not merely from their control over the money supply or demand deposits, but from their ability to contain the spread of systemic failure by being "lenders of last resort". In normal times, the Federal Reserve in the United States uses open market operations (i.e. buying and selling government bonds to influence the interest rate); but Akerlof and Shiller argue that the method of rediscounting (i.e. lending directly to troubled banks) matters more in times of crisis, because open market operations lose effectiveness once the interest rate has already fallen to zero.

In the postscript to chapter 7, Akerlof and Shiller provide recommendations for dealing with the 2007-2009 crisis (keep in mind the book was published in 2009). They argue that the biggest threat is the "credit crunch", as indicated by the drop in commercial paper outstanding. The roots of the crisis seem to lie in the increasing securitization of finance, with exotic derivatives and highly-leveraged "shadow banking" institutions (investment banks, bank holding companies, and hedge funds) which fueled a bubble that burst when the stories changed from "risk management" to "snake oil". The credit crunch implies that policy makers should aim not just to stimulate aggregate demand, but also to target the level of credit available -- for example by expanding the discount window (see rediscounting above), directly injecting capital into banks, and using government-sponsored enterprises (like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) to directly increase lending.

***

The Second Machine Age has a more cheerful tone, at least when it discusses the "bounty" of our future progress; in other words, we will have more, better, and cheaper stuff. This is because living standards increase in the wake of productivity growth (i.e. increased output per worker or unit of capital input), and computerization will boost productivity through better business processes and complementary innovations. But GDP should not be our only metric, because GDP leaves out important aspects of human well-being. For example, the prices of music, videos, games, and informational resources have fallen massively thanks to the digital economy (in many cases being free), yet this would seem to decrease the GDP while simultaneously improving our welfare. Social media and the "sharing economy" also represent growth that is poorly captured by GDP statistics. Therefore we need new economic metrics -- ones that make use of all the digital data (for instance, looking at Google searches or online prices).

But if you thought it's going to be all roses and sunshine, Brynjolfsson and McAfee also talk about the "spread"; in other words, the potential for economic inequality to accelerate. In the digital age, companies like Facebook and Instagram can become worth billions of dollars only a few years after being founded, with a relatively small number of employees. The combination of bounty and spread means that i) some people have the possibility to earn a million times as much as they could have before the second machine age; but also ii) that such digital innovations can leave a large number of people unemployed or living on reduced incomes. As the authors put it:

"Rapid advances in our digital tools are creating unprecedented wealth, but there is no economic law that says all workers, or even a majority of workers, will benefit from these advances." (p. 128)When we look at the evidence, we see that the median household income in the U.S. has fallen since 1999 while the share of income going to the top 1% has increased. Between 1983 and 2009, the bottom 80% of the income distribution experienced a net decrease in wealth, while the top 1% saw their earnings increase by 278% between 1979 and 2007. Overall, real GDP per capita has grown more than has median income per capita, and this trend is visible not just in the U.S. but also Sweden, Germany, and others -- which Brynjolfsson and McAfee attribute to the "exponential, digital, and combinatorial change in the technology that undergirds our economic system". There are winners and losers: the winners are those who have accumulated large amounts of capital assets and those superstars with special talents or luck; the losers include unskilled workers, workers without college degrees, and workers who perform routine tasks.

The gap between mere stars and superstars is perhaps even more striking: due to "winner-take-all" markets, the gulf between being number 1 and number 2 can be enormous. The very best authors, musicians, athletes, actors, app developers, and CEOs can make orders of magnitude more than the second or third best, even if the objective differences between them are tiny. Winner-take-all markets are prevalent in the digital economy because consumers care more about relative performance than absolute performance when goods and services are digitized, transport and communications are improved, and network effects are at play. Schumpeter's idea of "creative destruction" is becoming more relevant as more markets can be described by a power law distribution. The obvious question is whether the bounty will be larger than the spread, and here the authors are more pessimistic. They argue that it is plausible for the spread to erode the bounty by making political institutions more exclusive, such that upward mobility becomes ever more difficult and growth slows as a result. Additionally, technology itself can also cause unemployment (more so than globalization... indeed, developing nations will be particularly hard-hit by automation in the long-run). Hence, there is a strong case for intervention.

***

The topic of unemployment also crops up in chapter 8 of Animal Spirits, but here it is not about technological unemployment. Instead, Akerlof and Shiller focus on the human demand for fairness to explain why wage rates do not adjust to clear the labor market. In theory, people who cannot find jobs would simply ask for a lower wage (or seek jobs with fewer qualifications). If people are involuntarily unemployed, then according to the efficiency wage theory, that is because employers need to pay their workers above the market clearing rate in order for the workers to stay motivated, and hence the supply of labor exceeds the demand for labor. Firms willingly pay workers more than necessary, because workers who perceive their wage to be fair are less likely to quit or shirk on the job, but also because they feel a greater sense of duty toward their employer.

Fairness also interacts with money illusion when it comes to explaining why there is a trade-off between unemployment and inflation in the long run (called the Phillips curve). Wages tend to be downwardly rigid ("sticky") because people think that money wage cuts are unfair. This means that aiming for zero inflation is bad policy, because it would increase the unemployment rate (since firms' labor costs would increase) and thus reduce GDP. For this reason, we should be skeptical of Milton Friedman's natural rate theory, which defines price stability as zero inflation and assumes that people don't have money illusion.

Chapter 10 discusses why people fail to save or invest enough money to have a comfortable retirement. Young folks tend to neglect the power of compound interest, and this is arguably due to their animal spirits. The rate of savings varies across time and place, as a result of how we frame the stories about our lives and our future. People don't know how much to save, so they look to external cues -- credit cards telling them to spend, the default option in their savings plan, their current situation ("I'm still young!"), or in the case of Singapore and China, the government telling them to save. Some folks value frugality and others value consumption, and this can be influenced by national policy. All of this aside, one may get the impression that Akerlof and Shiller haven't paid attention to the trends of falling median incomes (making it harder to save) and rising technological unemployment pointed out by Brynjolfsson and McAfee... so what do the latter authors have to recommend?

***

The final section of The Second Machine Age talks about a number of interventions designed to maximize the bounty and mitigate the negative effects of the spread. For individuals, the authors recommend to race with the machines rather than against the machines. The example of Deep Blue is illustrative: even though IBM's computer beat chess world champion Garry Kasparov, it is still the case that a combination of human + machine can beat a computer alone (as in freestyle chess), because humans can uniquely contribute non-routine strategic guidance. Humans are still more creative and innovative than machines. Our senses still surpass the computer equivalents and we have an advantage in complex communications. Therefore, educational institutions should focus on instilling these skills, and failing that, individual students should use technologies like massive online open courses (MOOCs) to stand out and avoid being left behind.

On a policy level, Brynjolfsson and McAfee emphasize economic growth as a solution to short-term challenges. They make six recommendations: i) improve the standard of education with the help of MOOCs and higher teacher salaries; ii) promote entrepreneurship by reducing burdensome regulations and welcoming immigrants; iii) make it easier for job seekers to get matched with employers, for example using software; iv) increase funding for basic scientific research and offer prizes for innovations; v) ensure that infrastructure stays in excellent shape (and expand the H1-B visa program); and vi) use Pigovian taxes to discourage negative externalities, alongside taxes on economic rents such as land ownership.

In the long term, the machines are coming, and it is hard to predict exactly what will happen. In any case, the authors do not recommend a ban on technology or the overthrow of capitalism. However, they do consider a "basic income" scheme to be feasible, as long as people are still incentivized to work -- because work is beneficial for many reasons: self-worth, dignity, community engagement, healthy values, and so on. Unemployment contributes to more divorce, incarceration, etc. But perhaps a better alternative to the guaranteed universal income would be the negative income tax, which pays people who have an income below a certain threshold, kind of like a subsidy for labor. As for which kinds of jobs people will have, we can find inspiration in user-generated content and crowdsourcing (e.g. Mechanical Turk, TaskRabbit, Airbnb, uShip, Lyft, etc.). Other out-of-the-box ideas should be generated and experimented with, for example creating a "national mutual fund", incentivizing machines that augment rather than replace human abilities, starting a "made by humans" labeling movement, paying people to do socially beneficial tasks, providing vouchers for basic necessities, and so on.

The book concludes with a summary of the key points, along with a consideration of further risks: catastrophes cascading through tightly-coupled systems, tyranny, digital viruses, addictive gaming and social isolation, and even conscious machines. Yet the authors remain optimistic because "the arc of history is long but it bends towards justice". The future is not determined by technology, but by our choices; and therefore it is important to think about what we really value as individuals and as a society.

***

Yet human values are presumably related to human nature. And that often means irrationality, as we can observe by glancing at the fluctuations in stock prices. What chapter 11 of Animal Spirits tells us is that nobody has managed to explain financial price movements, and that this is perhaps because such prices aren't based on predictions of future divided earnings or economic fundamentals. Instead, stock price changes are correlated with various social changes. In particular, people tend to buy when prices are increasing and sell when prices are decreasing, resulting in price-to-price feedback. When stock prices rise, people save less and companies invest more in new equipment, resulting in price-to-earnings-to-price feedback between asset markets and the real economy. These feedbacks manifest in heightened or lowered confidence, i.e. animal spirits. Psychological feedback also influences oil prices, as in the stories of overpopulation and resource shortages in the 1970s that accompanied the oil crisis, and then died down in the 1980s when the price of oil fell. Corporate investments are often made on the basis of intuition, not mathematical analysis (due to Knightian uncertainty), and again confidence is relevant. For these reasons, it is important to regulate capitalism, lest we fall into another financial crisis.

Like stock markets, real estate markets are also volatile. The fever of the late 1990s and early 2000s is a case study in animal spirits: people told stories about how amazing homes and apartments were as investments, but failed to deliver rational arguments. People had the intuitive feeling that real estate prices could only go up. Part of the explanation lies in money illusion -- people fail to compare changes in land prices with changes in stock prices or the GDP (and so overestimate the real return). The feedback cycles that operate in financial markets also lead to overconfidence in real estate markets. When people have high hopes, it is easier for mortgage lenders to relax their standards and lend to nearly anyone, which can border on corrupt behavior.

Chapter 13 asks: why is there special poverty among minorities? Akerlof and Shiller identify two factors: stories and fairness. Being black, Hispanic, or Native American in the U.S. means that one is more likely to be unemployed, in prison, or addicted to drugs. This makes it easy for an us vs. them narrative to evolve, and for minorities to consider the economic system unfair. And because of this world-view, people adopt scripts regarding how they should behave and how the "others" ought to behave differently. Affirmative Action can help ameliorate the situation, because it symbolizes that whites care about blacks; as can well-designed schooling programs. Good government jobs and rehabilitative prisons could contribute to the effort. And making an effort is what matters.

Animal Spirits closes by reiterating the pitfalls of "rational expectations" and "efficient markets" theories, and calling on economists, pundits and policymakers to integrate animal spirits into macroeconomic theory. Akerlof and Shiller maintain that their theory gives a more accurate picture of the economic cycle:

"You pick the time. You pick the country. And you can be fairly well guaranteed that you will see at play in the macroeconomy the animal spirits that are the subject of this book." (p. 171).The fact that capitalism will sell people not just what they want but also what they think they want (e.g. snake oil), means that there is a role for the government to set the rules of the game, so that our animal spirits can be harnessed for the greater good.

***

I have so far summarized these two books more than I have critiqued them (a general trend in my book reviews), and the reason for this is that I want to represent the actual content of these books accurately to myself and my audience for the sake of reference. Needless to say, I don't necessarily hold the view that the underlying assumptions and omissions in the books I read should not be highlighted and challenged. In the case of Animal Spirits it is clear that the authors disagree with several aspects of mainstream macroeconomics, and they write in the introduction:

"This book is derived from a different view of how economics should be described. The economics of the textbooks seeks to minimize as much as possible departures from pure economic motivation and from rationality. [...] In our view economic theory should be derived not from the minimal deviations from the system of Adam Smith but rather from the deviations that actually do occur and that can be observed." (p. 5)And yet they also make it clear that they are not anti-capitalist per se:

"We agree regarding the wonders of capitalism. But that does not mean that there are not different forms of capitalism, with very different properties and benefits. [...] Yet we are currently not really in a crisis for capitalism. We must merely recognize that capitalism must live within certain rules." (pp. 171-173)Neither are the authors of The Second Machine Age opposed to capitalism. They write in chapter 14:

"We are also skeptical of efforts to come up with fundamental alternatives to capitalism. [...] Capitalism allocates resources, generates innovation, rewards effort, and builds affluence with high efficiency, and these are extraordinarily important things to do well in a society. As a system capitalism is not perfect, but it's far better than the alternatives." (p. 231)Therefore, both books fall into the (vaguely centrist or center-left) camp of "incremental tweaks" rather than "revolution". Naturally there are folks who will disagree with the stance, but personally I think it is reasonable. However, at the same time, the question of how AI and automation will change the world in the future is fascinating, and there is no doubt a risk of large-scale political upheaval. One book that is related to The Second Machine Age, which I have read a while ago, is called The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of Mass Unemployment and is written by software developer Martin Ford (published 2015/2016 by Oneworld Publications).

In The Rise of the Robots, Ford argues that machines are increasingly replacing workers, while at the same time median wages are lagging behind productivity growth and the costs of housing, education and healthcare are soaring. Not enough new jobs are being created to match population growth, and the concomitant long-term unemployment may have devastating effects on the consumer spending that drives the economy. An interactive combination of technological unemployment, rising inequality, an aging population, resource depletion and climate change could produce a "perfect storm", which may disrupt our entire system. Even white-collar jobs are at risk, because computers can already write articles (e.g. Quill), analyze mountains of data, manage projects (e.g. WorkFusion), answer questions (e.g. IBM's Watson), make scientific discoveries (e.g. genetic algorithms), and so on. Indeed, Martin Ford explicitly addresses Brynjolfsson and McAfee when he writes:

"Among economists who are tuned in to this trend, a new flavor of conventional wisdom is arising: the jobs of the future will involve collaborating with the machines. [...] Nevertheless, we should be very skeptical that this latest iteration will prove to be an adequate solution as information technology continues on its relentless exponential path." (pp. 124-125).Higher education and healthcare are two examples of industries which traditionally provided jobs to highly-skilled workers and are poised to be transformed by robots, AI and big data. Workers are also consumers, so a massive rise in inequality could undermine economic growth to the point where a significant number of people would be economically disenfranchised. We might even end up with a techno-feudal society wherein a small plutocracy live in guarded elite communities while the rest starve outside the gates... although an extreme scenario, the point is that our future prosperity is not guaranteed. Even the topic of superintelligence crops up in Ford's book (but he calls it highly speculative). Ford argues for a basic income guarantee which incorporates incentives for education and community service, perhaps funded by taxes on emissions, land, capital gains, and financial transactions. In this regard, his recommendations are similar to those of Brynjolfsson and McAfee.

|

| Similar books |

"While endorsing the importance of animal spirits and limited rationality, we do not agree with Akerlof and Shiller that if individuals were rational and had only economic motives then there would be little role for the government in regulating financial markets. Problems of imperfect and asymmetric information are pervasive and are particularly important in financial markets." (p. 245)Thus we see that books can be in broad agreement while differing on particulars.

How do I personally rate these books? Well, Animal Spirits and The Second Machine Age both get 4/5 stars because they are informative and smart. I prefer the writing style of Brynjolfsson and McAfee, and sometimes Akerlof and Shiller can be a bit dry; but in general, both books are clearly written and organized. The reason why neither gets full points is that much of the content isn't new or original enough -- after all, behavioral economics has been around for a while, and so have arguments about robots taking over our jobs. Nonetheless, these two books have unique approaches to presenting their respective theses, and so are still worth reading. And when read together, these books will help you understand the short-to-medium-term fluctuations of the economy in terms of human psychology (our animal spirits), and the medium-to-long-term changes in the structure of the economy in terms of technological progress (the machines). Both can be scary.

Comments

Post a Comment