Immortal Cooperation

Book Review:

Richard Dawkins, "The Selfish Gene", Oxford University Press, 2016 (40th anniversary edition).

If the name Richard Dawkins rings a bell, it might be because he is a prominent atheist and author of The God Delusion. But he is also a well-respected evolutionary biologist at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of the Royal Society. The book that launched him to fame, all the way back in 1976, was The Selfish Gene, which today can be bought in its 40th anniversary edition. It has been recommended as reading for aspiring rationalists, and following Bill Bryson's "A Short History of Nearly Everything" I've been more keen on natural sciences. So, today I'll explain to you the hype behind The Selfish Gene.

The first thing to address is the title, since it tends to confuse people. This is not a book about how people are selfish; it is a book about how genes are "selfish" in the sense that they care only about increasing their own survival prospects. Of course, genes don't really care about or want anything -- it is just a convenient metaphor. But the consequence of a self-replicating molecule is that it will become more common the more stable it is ("stable in that either the individual molecules lasted a long time, or they replicated rapidly, or they replicated accurately" -- p. 23). Moreover, because resources (such as purines and pyrimidines) are limited, different varieties of replicator must compete for them, and the "fittest" become more numerous. This is Darwinian evolution by natural selection.

Which brings us to the second point to understand: Richard Dawkins was writing this book at a time when many biologists were arguing that organisms evolve to do things "for the good of the species". This is called "group selectionism", and it has been used to explain why worker bees sting (even though it is suicidal), why birds put themselves in danger by giving an alarm call, or why mothers incur great cost to feed and incubate their children. The Selfish Gene may be interpreted (partly) as an attack on the group selection theory: Mr. Dawkins believes that apparently altruistic behavior can be better explained through the theory of gene selection or individual selection. (See also Yudkowsky on The Tragedy of Group Selectionism.) Indeed, the purpose of the book can probably be summarized as being to "show how both individual selfishness and individual altruism are explained by the fundamental law that I am calling gene selfishness" (p. 8, italics in original). To be clear, the terms "gene selection" and "individual selection" are for the most part used interchangeably, because living creatures ranging from bacteria to humans may be regarded as "survival machines" for genes. That is what we really are: containers and vehicles.

The fact that so many genes can share the same vehicle (i.e. organism) means that self-interested genes in a sense cooperate with each other. Therefore, as Dawkins himself admits in an introduction to a later edition, he might as well have titled the book The Cooperative Gene. He also could have called it The Immortal Gene, since the "immortality" of genetic information through the generations is a key theme. Ultimately he went with The Selfish Gene to emphasize the fact that natural selection happens not on the level of the ecosystem, the species or the group, but the gene. Oh well.

Dawkins jokes in Chapter 3 that he could even have titled the book "The slightly selfish big bit of chromosome and the even more selfish little bit of chromosome". In the chapter he explains how DNA molecules are made from long chains of nucleotides, which are strung together in sequences called genes, and those genes in turn make up chromosomes. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes (so 46 in total). From each pair, you get one chromosome from your father and one from your mother. This is because of sexual reproduction, which "shuffles" genes such that only relatively small genetic units can last for many generations. (A long unit is more likely to be split in the testes or ovaries.) Hence, the "little bit of chromosome" that Dawkins identifies as the gene. Chapter 3 is perhaps the most technical in the book, and the rest of the book is less about genes per se and more about animal behavior as caused by genes. Richard Dawkins is, after all, an ethologist.

In Chapter 4, Dawkins talks about animals as gene survival machines. He writes:

"Just as it is not convenient to talk about quanta and fundamental particles when we discuss the workings of a car, so it is often tedious and unnecessary to keep dragging genes in when we discuss the behaviour of survival machines. In practice it is usually convenient, as an approximation, to regard the individual body as an agent 'trying' to increase the numbers of all its genes in future generations." (p. 60)After some discussion of muscles, neurons and sense organs, the author introduces the principle of negative feedback. This simply says that a machine works to reduce the discrepancy between the current state of affairs and the "desired" state or "aim". It explains why guided missiles and chess-playing computer programs appear to exhibit "purposeful" behavior despite lacking consciousness. The key idea is that, although such a computer has been programmed beforehand, it operates on its own. Likewise, genes give general instructions to their survival machines but don't directly control them from moment to moment. Genes are too slow to pull the puppet strings, so they have programmed survival machines to learn, predict, and at least in the case of humans, to imagine. Of course, genes primarily program survival machines to... well, survive; to find food, avoid predators and disease, to reproduce, and so on. It is for this reason that animals may be said to behave selfishly.

The chapters that follow deal with conflicts of interest between individuals: Dawkins explores the topics of aggression (Chapter 5), kin altruism (Chapter 6), family planning (Chapter 7), parent-offspring conflicts (Chapter 8), the "battle of the sexes" (Chapter 9), and reciprocal altruism in groups (Chapter 10). In each case, his approach is informed by the neo-Darwinist tradition of Ronald A. Fisher, William D. Hamilton, George C. Williams, John Maynard Smith, and Robert L. Trivers. These are, according to Dawkins, the "heroes" of the book.

***

When it comes to aggression, things like murder and cannibalism occur less often in nature than one might expect. Animals don't kill rival members of their species at every possible opportunity; indeed, animal fighting often seems restrained, similar to how boxers use gloved fists. Fighting uses up time and energy, and by killing one rival you might actually be helping another rival. This kind of cost-benefit calculation has been studied through the lens of game theory by J. Maynard Smith and others. The key idea is the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), which refers to a behavioral policy followed by most members of a population, and which cannot be "beaten". For example, in a population consisting almost entirely of aggressive players, a coward can prosper by getting hurt less often than the other players. Thus, the "coward" genes may start to spread through the population. But if the population were fully coward, then a single aggressor would enjoy a huge advantage in gaining resources, and his genes would spread. So, the population will tend toward a stable ratio of the two strategies, or an equilibrium. Of course, real life is more complicated -- animals can employ a mix of strategies, individuals differ in terms of strength, they can remember who is dominant, and so on. But this is a good model that can explain why cannibalism is relatively rare.

What about a scenario in which the individuals are close relatives who share much of their genes? When a gene has replicas of itself in other bodies, its selfish "aim" (to multiply) can manifest as altruistic behavior by the bodies. For instance, an individual may sacrifice himself in order to save ten close relatives, but it would be a net positive for the kin-altruism gene. In fact, we can calculate the threshold where a suicidal altruistic gene becomes successful by looking at the index of relatedness between individuals (i.e. the chance of a rare gene being shared between the individuals). For parents, children and siblings this is 1/2 or 50%. For uncles, aunts, grandparents, grandchildren, nephews, nieces, and half siblings it is 1/4. First cousins and great-grandchildren are at relatedness 1/8, and so on. One of the conclusions is that parental care is simply a special case of kin altruism, and that there is no hard line between family and non-family. This argument was made by W.D. Hamilton (who also inspired Maynard Smith to formulate the ESS). Again, reality is more complex because individuals may take into account all kinds of risks and benefits to themselves and others (such as life expectancy), and relatedness isn't always easy to estimate. This could be why parental care is more common in nature than brother/sister altruism.

Speaking of parental care, Richard Dawkins makes a distinction between caring for existing children and bringing new ones into the world. Child-bearing decisions are about whether the survival machine should reproduce, while child-caring decisions include feeding a child and so on. Because an individual has limited resources, they need to make trade-offs; and in this context the so-called "group selectionists" such as V.C. Wynne-Edwards have argued that animals deliberately reduce their birth rates for the good of the group. The theory is that uncontrolled population growth will lead to mass starvation, clearly not in the species's interest. According to Dawkins, the selfish gene theory does not disagree that animals engage in "birth control" or "family planning" -- it only differs on the reasons for this. Restrained breeding is not an altruistic practice for the good of the group as a whole; it is a strategy to maximize the number of surviving children of the individual. Simply put, having too many babies results in less efficient caring. This argument was made by David Lack, who like Dawkins's doctoral supervisor Niko Tinbergen is not one of the "named heroes" of the book, but who nevertheless seems to have had a great influence on the author.

Although parents want their children to survive until adulthood, it is not necessarily the case that a mother will treat all her offspring equally or that members of a family will always cooperate towards the same optimum. The concept of parental investment, as formulated by R.L. Trivers, says that the more food and energy a parent invests in a child's chance of survival, the less they can invest in other offspring. At face value, a mother has the same relatedness to all her children and so should not have favorites. But of course, some children may be more likely to survive than others. Moreover, a child might selfishly want more attention for himself, and therefore try to grab more than his fair share by screaming, cheating, deceiving, or even blackmail (e.g. baby cuckoo birds who scream to attract predators). In this sense, there will be a parent-offspring conflict or "battle of the generations" between manipulative children and parents who try not to get fooled. According to R.D. Alexander, parents enjoy an advantage due to being bigger, stronger, and worldly-wiser. Dawkins writes that the argument is "well taken", but that there is still "no general answer to the question of who is more likely to win the battle of the generations" (p. 180).

One of the more cynical chapters in the book talks about the "battle of the sexes", i.e. conflicts of interest between mates. Referring back to parental investment, Trivers has suggested that each parent has a genetic incentive to invest less than his or her fair share of costly resources into rearing their children, and instead, to go off to copulate with other sexual partners. In animals as well as plants, one sex (which we call "male") tends to have smaller and more numerous gametes, which implies they can have more children. Despite being more "expendable", males tend to be just as common as females in the population because having mostly daughters is not an evolutionarily stable strategy (i.e. in that scenario, a gene for having sons would be at an advantage). This reasoning for a stable sex ratio of 50:50 is due to R.A. Fisher (who also used the phrase "parental expenditure" even before Trivers). However, since eggs are a bigger investment than sperms, it is easier for males to get away with abandoning their partners and children. They have less to lose. On the other hand, a female may evolve strategies to counter this, for example tricking another male into adopting her child, or simply refusing to copulate with unfaithful males (who may be identified as the impatient ones). In species where males do get away with exploiting the females, the females may choose to let only the "best" males copulate -- in the case of elephant seals, for instance, most males go without copulating. Females could look for signals of good genes like strong muscles or, as Fisher suggested, sexual attractiveness to other females (with the peacock's tail being a clichéd example). An alternative to Fisher's "runaway process" comes from Amotz Zahavi, whose handicap principle postulates that males will evolve handicaps (such as inordinately cumbersome tails) precisely because those features are hard-to-fake signals of quality.

Ultimately, mates still have a lot to gain from cooperation, and so do survival machines who live together in groups. Herds of mammals, flocks of birds, schools of fish and swarms of insects are common in nature. According to W.D. Hamilton, herds form when selfish individuals seek to minimize their exposure to predators. However, to explain altruistic bird alarm calls, Dawkins offers two explanations: first, a bird may be warning his companions to keep quiet; and second, the bird might be urging the rest of the flock to follow him, so as to avoid being the odd one out. But what about the conspicuous stotting high jumps of the gazelle? Again, A. Zahavi promoted the idea that this is a signal of health and youth, meant to persuade a predator to choose another prey. Maynard Smith and Dawkins were both initially skeptical of Zahavi's theory, but Dawkins notes in a later edition of The Selfish Gene that Alan Grafen has translated the idea into a viable formal model. In any case, the point is that these behaviors have selfish reasons. Even symbiotic relationships between members of different species (e.g. cleaner-fish) can be explained by the theory of selfish genes when we look through the lens of mutually-beneficial reciprocal altruism. G.C. Williams wrote that an animal helped by its friend can remember to pay back the good deed later. R.L. Trivers took the concept further by showing how reciprocal altruism can be a stable unconscious strategy if individuals reciprocate back-scratching but hold grudges against cheaters. Which brings us to...

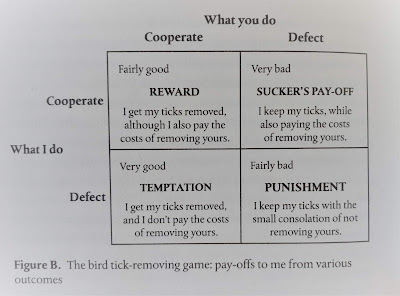

...the idea that "nice guys finish first". For the second edition of The Selfish Gene (published 1989) the author added two chapters and extensive endnotes. The first of the additional chapters, Chapter 12, deals with Prisoner's Dilemmas in nature. Dawkins has been inspired by the work of W.D. Hamilton and political scientist Robert Axelrod, who cooperated on running a tournament of programmed strategies to see which would "win" the most points. The result was a paper titled "The evolution of cooperation", and it showed that a strategy called Tit for Tat generally does best. In a simple Prisoner's Dilemma, the payoff matrix looks like this:

Here, the rational move is to defect regardless of what the other player might do. However, when the game is repeated indefinitely -- i.e. we have an Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma -- there is room to build trust. Tit for Tat begins by cooperating, and in each subsequent round copies the previous move of the other player. It is therefore "nice" in the sense that it never defects first, and it is "forgiving" because it doesn't hold a grudge. In fact, not only Tit for Tat but also other nice and forgiving strategies scored better on average in Axelrod's tournaments than the "nasty" strategies. What about the natural world? Well, Dawkins names numerous examples, including the case of blood-sharing vampire bats. Sometimes vampires get lucky and find a surplus of blood to feed on, and sometimes they return to the roost with an empty stomach. It turns out that vampires save each other's lives by regurgitating and donating some of the blood to their less fortunate roost-mates, in return for a gift on their own unlucky nights. Vampires, then, could be symbols for mutual cooperation and reciprocal altruism.

Jumping back to Chapter 11, Richard Dawkins finished the original edition of The Selfish Gene by introducing the revolutionary concept of the meme, short for "mimeme", which comes from the Greek root for imitation. To be clear, Dawkins is not talking about dank internet memes, but about any unit of cultural transmission (e.g. ideas, catch-phrases, fashions, tunes, architectural styles etc.) that is self-propagating. Just as a gene, in G.C. Williams's definition, is a portion of a chromosome with enough longevity across generations to serve as a unit of natural selection, so a meme is a replicating unit that serves as the basis for cultural evolution. Memes compete against each other for space and attention on human brains (while genes compete against alleles for the same chromosomal slot). What is interesting is that memes and genes may even oppose each other in some cases -- celibacy, for example, might not be genetically selected for but could still spread among priests through memes. The uniquely human capacity for conscious foresight and genuine altruism means that we should be optimistic about our potential to rebel against the short-term selfish interests of our genes.

Finally, in Chapter 13, Dawkins summarizes the argument from his second book, The Extended Phenotype, which he considers probably his finest work. The title of this chapter, "The long reach of the gene", alludes to the core idea. Essentially, genes are susceptible to natural selection only because of the differential effects they have on organisms' bodies -- in other words, their phenotypes. The phenotypic effects of a gene might include eye color, running speed, body size and so on. But Dawkins asks: why stop there? Shouldn't we consider all the effects that a gene has on the world, not just the effects on the individual body in which it sits? In other words, Dawkins argues that genes may have extended phenotypic effects, for example beaver dams, bird nests, and caddis houses. This means that we could speak of genes "for" house shape just as we speak of genes for leg shape. Moreover, the genes in one organism may have extended phenotypic effects on the body of another! Parasites are a great example: a parasitic barnacle that castrates a crab will change the body of the crab in such a way -- making it divert resources -- as to benefit the parasite genes (at the expense of the crab's reproduction). Thus, Dawkins arrives at his central theorem of the extended phenotype:

"An animal's behaviour tends to maximize the survival of the genes 'for' that behaviour, whether or not those genes happen to be in the body of the particular animal performing it." (p. 327)Now we can begin to understand why genes cooperate to make large vehicles. According to Dawkins, the key is that all genes in a body leave the body and are transmitted to future generations through the same method, e.g. sperm and eggs. They share a "common destiny", so they work together to make a coherent and purposeful vehicle. But this also means that parasites will cooperate with their hosts if they are squeezed through the same reproductive bottleneck (which is why Dawkins speculates that STDs might increase the libido of their hosts). The extended phenotypic effects of genes remind us that the gene's view comes before the individual organism.

***

The 40th anniversary edition of The Selfish Gene includes an Epilogue, in which the author offers some reflections on recent developments in genomics. Ultimately, the selfish gene theory is vindicated, and Richard Dawkins goes so far as to suggest that it would be "a valid account of life on other planets even if the genes on those other planets have no connection with DNA" (p. 349). But it can also tell us much about our own ancestry, especially in the case of mitochondrial DNA (which we inherit only from our mothers). A technique called "coalescence analysis" can look at your genome and infer demographic details of prehistoric humans! For example, if many chromosomal pairs of your genes coalesce in a common ancestor of about 60,000 years ago, it suggests that the population was probably small at that time. And by comparing your genome to that of someone from a different part of the world, we can even add a geographic dimension.

So, the gene's eye view of evolution can tell us about selfishness, altruism, and even historical demography. But what it does not tell us is how we morally ought to behave; it does not say that life is purposeless or that we need to follow right-wing policies. Dawkins makes it clear in Chapter 1 that he is not advocating a morality based on evolution, nor is he saying that our behavior is inevitably determined by genes alone. Nonetheless, some critics have missed this point. At the same time, the book has also received a lot of praise over the years. Here are some samples:

- From Robert Trivers's foreword: "With a confidence that comes from mastering the underlying theory, Dawkins unfolds the new work [in Darwinian social theory] with admirable clarity and style" (p. xxvi).

- From W.D. Hamilton's review: "It succeeds in the seemingly impossible task of using simple, untechnical English to present some rather recondite and quasi-mathematical themes of recent evolutionary thought" (p. 459).

- From John Maynard Smith's review: "The Selfish Gene was unusual in that, although written as a popular account, it made an original contribution to biology. [...] What it does offer is a new world view" (p. 463).

- From Sir Peter B. Medawar's review: "The more clearly we understand the selfishness of the genetic process, however, the better qualified we shall be to teach the merits of generosity and co-operativeness and all else that works for the common good, and Dawkins expounds more clearly than most the special importance in mankind of cultural or 'exogenetic' evolution" (p. 458).

Speaking of Trivers, the rationality community has also taken note of Trivers's theory of self-deception, which proposes that animals evolved to be unconscious of (some of) their own motives, so as to better deceive others. This is also the basis of Robin Hanson's argument that Politics isn't about Policy but about signalling our affiliations to gain status. I've gone on a bit of a tangent, but this can be linked back to The Selfish Gene when we consider all the conflicts of interest discussed in the book, or the Zahavi-Grafen "handicap principle". The point is that the selfish gene theory has profound implications.

(One interesting implication relates to aging; Medawar, Williams and Hamilton have all theorized that senescence is caused by lethal and semilethal genes that are stable in the gene pool because their effects come into play only when the survival machine is past reproductive age.)

I agree with the reviews quoted above, and I do not have much to add, except to say that Dawkin's careful reasoning is evident in his writing. On the negative side, the book can sometimes be a bit hard to follow, especially given the lack of organizing sections and headings in the chapters. There are many walls of text to be seen. It is also somewhat inconvenient that many of the updates of the second edition are in the notes at the end (and there are 75 pages of notes, not including the bibliography!) rather than integrated into the text. But the content is still fascinating, and the reader will emerge from the experience with a greater sense of awe at Mother Nature.

Comments

Post a Comment