Around the World in Ten Dramatic Instincts

Book Review:

Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Rönnlund, "Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World -- and Why Things Are Better Than You Think", Flatiron Books, 2018.

In recent months I've looked at rules of thumb for thinking more clearly about money and about rare yet impactful events. Today I'm expanding that toolkit of heuristics with Factfulness, a book by Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Rönnlund. The book has received praise from the likes of Bill Gates and Barack Obama, but I was also keen to read it because I knew about Hans Rosling from his first TED Talk (which I watched years ago in Geography class). And yes, Factfulness was a joy to read.

You probably know that climate experts believe that the average global temperature will get warmer over the next century. But did you know that in the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has almost halved? Or that 80% of the world's one-year-old children have been vaccinated against some disease? These are the kinds of questions that the Gapminder Foundation asks in its test about basic global patterns and trends -- a series of 13 fact questions that most people get wrong. When the climate question is excluded, it turns out that only 10% of people (from a sample of 12,000 people) get more than 4 out of 12 questions correct! Here are a few more questions:

- In all low-income countries across the world today, how many girls finish primary school? Is it A: 20 percent; B: 40 percent; or C: 60 percent? The most common answer people gave was A, but only 7% of people picked the correct answer, C.

- How did the number of deaths per year from natural disasters change over the last hundred years? A: More than doubled; B: Remained about the same; or C: Decreased to less than half? Again, the correct answer is C, yet only 10% of people here picked the right answer.

Why do people score so poorly? Well, according to the authors, it has to do with our "ten dramatic instincts". These are partly based on research by cognitive scientists including Dan Ariely, Steven Pinker, Daniel Kahneman, Jonathan Haidt, Philip Tetlock and Elliot Aronson. These instincts need to be taken into account when teaching people facts about the world. Our over-dramatic worldview needs to be countered by a fact-based worldview, but there are certain thinking tools and rules of thumb that make this easier. The Rosling family calls it "Factfulness": a way to control one's dramatic instincts and get the world right without having to learn the latest information by heart.

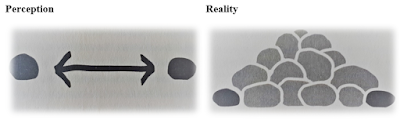

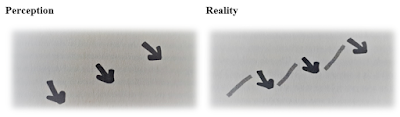

For many readers, this book may be quite eye-opening, which is why I will use a "before vs. after" metaphor in summarizing it. The illustrations that follow are all in the book -- for each chapter there is a pair. The first of each pair starts the chapter, and the second is at the end of the chapter. The second drawings for all the ten instincts (which I have chosen to label "reality") are repeated on page 256, which summarizes the ten Factfulness rules of thumb: look for the majority -- expect bad news -- lines might bend -- calculate the risks -- get things in proportion -- question your categories -- slow change is still change -- get a tool box -- resist pointing your finger -- take small steps. Let's dive in.

***

The Gap Instinct

- Level 1: There are about one billion people who earn below $2 per day (adjusted for price differences) as of 2017. It is common for people on this level to walk barefoot and cook by burning firewood.

- Level 2: People on this level earn an average of $4 per day and are able to afford food they didn't grow themselves, as well as shoes and (shared) toothbrushes. They may save up to acquire bicycles, gas stoves, and mattresses. About 3 billion people live like this.

- Level 3: At an income of $16 a day, the two billion people on Level 3 are able to get stable electricity, cold water from a tap, and to save up for motorcycles or even short vacations.

- Level 4: This is the top one billion people, who earn above $32 a day. These folks are highly educated, capable of affording cars and restaurant meals, and have hot water indoors.

To control the gap instinct, you should beware comparisons of averages and comparisons of extremes. It may be true that men on average have higher SAT math scores than women, but when you look at the range (i.e. spread) of scores you'll see a huge overlap. And while comparing extreme examples like the richest and poorest in Brazil may provide for a dramatic story, it misses the big picture: that most people are in the middle, and are "slowly dragging themselves toward better lives" (p. 39).

The Negativity Instinct

The news we receive tends to be bad news, because such information is simply more likely to reach us. There are three reasons for this: firstly, we romanticize the past and forget that things used to be worse just a couple of generations ago; secondly, journalists and activists selectively report on disasters and suffering because such stories make the front page; and thirdly, people feel guilty saying that things are getting better when there are still many problems. As a consequence, most people believe that the world is getting worse, which creates stress for no good reason.The solution is to use statistics as therapy. The data shows that the world is getting better: extreme poverty (living on Level 1) was life for 85% of humanity in the year 1800, but this has dropped to only 9% in 2017. Over the same period, average life expectancy increased from 31 years to 72 years. And there have been many more improvements: legal slavery, oil spills, HIV infections, the price of solar panels, child mortality, battle deaths, leaded gasoline, countries with the death penalty, plane crash deaths, child labor, nuclear warheads, smallpox, smoke particle emissions, deaths from disasters, ozone-depleting substances, and hunger have all decreased. The number of scholarly articles published per year, new movies and music released, voting rights for women, cereal harvest yield, protected nature reserves, monitored species, adult literacy, share of humanity living in democracy, child cancer survival rates, electricity coverage, girls in school, people with mobile phones and the Internet, clean water, and vaccination rates have all increased. Even the number of guitars per capita (a proxy for development) is increasing!

Hans Rosling does not consider himself a naive optimist, but a possibilist -- someone who believes that further progress is possible, given a reasonable and constructive view about how things are. The negativity instinct is dangerous because it can lead us to lose hope or try counterproductive methods. That's why we should learn to control the instinct by realizing that things can be both bad and also getting better at the same time. It's a distinction between level and direction. Additionally, it helps to keep in mind that more bad news may not imply a worsening world; it could also be the product of better surveillance of suffering.

The Straight Line Instinct

Somewhat related to the negativity instinct is the assumption that a line will just continue straight, even though many trends in reality are not straight lines. For example, it is a common misconception that the world population is just increasing and increasing, which leads people to think we need drastic action. But Rosling gives a colorful analogy: a child grows quite rapidly in the first six months of its life, yet of course we wouldn't expect it to keep up the same rate. Unfortunately, people are less familiar with the statistics, which show that the rate at which the world population is growing, is slowing down. The UN forecasts that the population curve will flatten out between 10 and 12 billion people by 2100, largely thanks to the fact that the average number of babies per woman has dropped from 5 births in 1965 to just 2.5 in 2017, and is expected to continue declining.This is important, because some folks seem to think that the way to save the planet from overpopulation is to stop saving poor children. Rosling rebuts this:

"Every generation kept in extreme poverty will produce an even larger next generation. The only proven method for curbing population growth is to eradicate extreme poverty and give people better lives, including education and contraceptives." (p. 91)To control the straight line instinct, remember that curves come in different shapes. Some lines do happen to be straight, such as the relationship between wealth (GDP per capita on a logarithmic scale) and health (years of expected life), or wealth and average years of schooling. However, there are also S-shaped curves: for example, countries at Level 1 struggle to afford fridges or vaccines for everyone, but then the curve bends rapidly at Level 2 and flattens off at Levels 3 and 4, where everyone has these things. The reverse of an S-bend is a slide, such as the graph of babies per woman. Some relationships have a hump shape, like dental health (tooth decay), motor vehicle deaths and child drownings. They are low at Levels 1 and 4 (perhaps for different reasons) but high at Levels 2 and 3. Finally, there are doubling lines, for instance the share of income people spend on transportation and their carbon dioxide emissions, which approximately double at each level of income. Sometimes, a doubling pattern needs to be taken seriously, like the case of the Ebola epidemic.

The Fear Instinct

We have seen the three Mega Misconceptions, as Rosling calls them: that the world is divided in two, that the world is getting worse, and that the world population is just increasing and increasing. Apparently the rest of the book deals with merely regular misconceptions... nevertheless important ones. Take the fear instinct, for instance. Our evolved fears about physical harm, captivity and contamination make it easy for dramatic stories (e.g. earthquakes and plane crashes) to break through our attention filters. The result is a distorted picture of the world; we don't hear about true stories like the decline in deaths from natural disasters, the decline in plane crash deaths, or the fall in battle deaths. Our fear of contamination can make us irrationally distrust nuclear power and vaccines. Terrorism gets a lot of media coverage, and even if it has been increasing in places like Iraq, on a global level it still accounts for 0.05 percent of deaths, and in the U.S. you are more likely to be killed by a drunk person (through homicide or road accident).To control the fear instinct, we need to recognize that the most frightening things are not necessarily the most dangerous ones. Fear should be directed at real risks, which can be calculated by multiplying danger and exposure. Make decisions when you're calm.

The Size Instinct

Hans Rosling continues putting journalists to shame when he says: "It is pretty much a journalist's professional duty to make any given event, fact, or number sound more important than it is" (p. 128). The size instinct relates to the identifiable victim effect as well as the fact that a number without context feels important. It makes people pay too much attention to saving an individual child, while neglecting that they can save more lives by using scarce resources on vaccinations, nurse education and primary schools (not fancy hospitals). It also makes people underestimate the global proportion of people with electricity, and overestimate the proportion of immigrants in their countries.The obvious solution is to get things in proportion -- to always compare a lonely number to something else. For example, 4.2 million babies died in 2016, which sounds enormous, but in 1950 the number was 14.4 million!

When you look at a long list of causes of death, sources of energy, or the line items in a budget, remember that not all items on the list are equally important; often the 80/20 rule applies (whereby a few items account for a large share of the total).

Finally, use rates instead of absolute amounts, because they allow for more meaningful comparison between differently-sized groups. For example, you can calculate the child mortality rate by dividing the number of child deaths by the number of births. In the case of 1950, this works out to 15%, while for 2016 it is 3%. This shows us that the lower amount of dead children is not simply due to fewer births. The total amount of carbon dioxide emissions of a country is also different from the emissions per person.

The Generalization Instinct

We automatically (and necessarily) categorize things all the time, but generalizations can be misleading. For example, dividing the world into "us" and "them" can cause companies to overlook profitable investment opportunities. Generalization can even be dangerous -- Rosling tells an anecdote of a Swedish medical student whose leg was nearly crushed because she assumed that the elevator doors in India would have sensors on them. Incidentally, traveling the world (or traveling virtually by checking out the photos on Dollar Street) is a good way to check your assumptions. What you may notice is that a person's country, culture or religion matters less than their income; families living on Level 4 around the world tend to have very similar kitchens, bedrooms and bathrooms.There are more ways to question your categories: (i) look for differences within groups and similarities across groups (for instance, Tunisia does not have the same "African problems" as Somalia); (ii) be wary when someone talks about "the majority", because there is a difference between 51 percent and 99 percent; (iii) don't draw conclusions about a group based on a single vivid example (e.g. not all "chemicals" are harmful); (iv) don't assume that your experience is "normal" or that people in Levels 2 and 3 use dumb solutions; and (v) try not to generalize across incomparable groups, such as sleeping babies and unconscious soldiers.

The Destiny Instinct

The destiny instinct is "the idea that innate characteristics determine the destinies of people, countries, religions, or cultures" (p. 167). The idea that things never change plays a role in the gap instinct and the generalization instinct, and it makes us slow to update our knowledge in the face of revolutionary transformations. For example, some people believe that Africa will never catch up to Europe, or that the "Islamic world" has fundamentally different "values". However, the facts show that countries like Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya and Bangladesh have been growing their economies faster over the past decade than the West. And the number of babies per woman has dropped as income has risen, even in Muslim populations! Hans Rosling writes that a good way to control the destiny instinct is to "talk to Grandpa", because our grandparents' values are often different from our own -- highlighting the fact that values change all the time. For instance in Sweden, the culture of the 1950s was much more sexually conservative than it is today.Other tips include remembering that things change slowly, yet small change is still change, and can gradually add up to big change. And since things change, you should be prepared to update your knowledge. Look for examples of how cultures have changed (e.g. attitudes toward homosexuality). Have vision.

The Single Perspective Instinct

Journalists, subject experts, activists, and political pundits all suffer from the unfortunate tendency of seeing the world through a single perspective. For professional or ideological reasons, or simply to save time, they reduce every problem to a single cause with a single solution -- such as always supporting more deregulation, or always more redistribution. Experts can of course be useful, but they are only experts within their own fields, and even Nobel laureates get the Gapminder questions wrong. Activists play an important role in improving the world, but they also tend to exaggerate the problems they devote themselves to. So, if you want to understand reality, be careful here.There is no one solution that will solve all problems. Some folks get fixated on the numbers, while others are fixated on a particular kind of medicine. But while data is essential, you cannot understand the world with only numbers; and trying to eradicate tuberculosis may be less fruitful than gradually improving primary healthcare for all (such as through cheaper drugs and better transport to hospitals). The Cuban government considers Cuba to be the "healthiest of the poor", but another perspective is that Cuba is the "poorest of the healthy". Inversely, the United States has a lower life expectancy than many other countries on Level 4 despite spending more per capita on care (because it lacks public insurance). The point is that the ideologues who see government or the market as the solution to all problems are both wrong -- according to Rosling, we need to look case-by-case. Even democracy is not necessary for economic development. Reality is complicated, so we need to look at problems from many angles: we need a toolbox rather than a hammer.

Be humble about what you don't know. Test your ideas and seek out people who disagree with you or come from other fields. At the same time, remember that others are also limited in their expertise, and that some people use utopian visions to justify terrible actions.

The Blame Instinct

Speaking of simplification, when things go wrong we tend to look for the malevolent or negligent agent responsible. (Conversely, when things go well, we quickly give credit to an individual.) Blaming one party makes the world feel more predictable, even when the truth is usually more complex. The "blame game", according to Rosling, often serves to confirm preexisting biases -- people like to blame evil business, the media, or refugees and foreigners. Likewise, political leaders and CEOs often claim to have more agency and power than they actually have. But rather than focusing on a hero or scapegoat, we will be better able to prevent future problems if we look at systems. For example, societal institutions (e.g. civil servants) and technology have played important roles in global development.To control the blame instinct, resist pointing your finger at heroes or villains. Remember that journalists are (mostly) not trying to deceive you, but give you a skewed worldview because (a) their incentive is to compete for your attention, and (b) they fall for the same misconceptions as everyone else. When experts and documentarians make mistakes, it's usually not out of bad intentions. There is little to gain by demonizing them, and doing so stops you from looking for other explanations (akin to Yudkowsky's notion of motivated stopping). Look for multiple interacting causes, or systems.

The Urgency Instinct

At some points we feel like we have to do something, or else... But the fear of the worst-case scenario leads to the urgency instinct: the feeling that we must decide quickly or lose the chance forever. This makes us think things through less carefully, and consequently make worse decisions. Fortunately, it is almost never the case that a decision is truly urgent. So, the next time a salesperson or activist urges you to "act now!", remember that the stress can block you from thinking clearly -- you should take a breath, and ask for more time and information. Ask for data, but make sure you aren't getting only the worst-case forecast; insist on a range of predictions with a clear indication of the level of uncertainty. Useful data is accurate, relevant, and acknowledges uncertainty about the future.If you are an activist, be careful not to cry wolf too many times, because at some point people will stop listening. Hans Rosling does not support scare tactics like blaming all global problems, including refugees, on climate change. In the long-run, they only harm the reputation and credibility of people who care about the risk of climate change. Try to focus on realistic, sensible solutions; this usually means step-by-step practical improvements. Ask how an idea has been tested, and what the side effects might be.

Importantly, Rosling is not arguing that we should not be worried about big global risks. He writes that there are five "mega killers" (or six if you count the unknown) that are somewhat likely: global pandemic, financial collapse, world war, climate change, and extreme poverty. But he also writes that these risks "are too big for us to cry wolf" (p. 241). We should keep our eyes on them while maintaining cool heads, robust data, and global collaboration. That requires controlling the urgency instinct.

***

For all these reasons, things are better than we tend to think. Most people in the world today do not live in extreme poverty; multiple indicators show that the world is getting better; the population won't just keep growing; frightening things (e.g. plane crashes and natural disasters) are less of a risk than you might think; at some point in the future the majority of people on Level 4 will live outside the West; people with similar income levels around the world tend to live similar lives; cultures may change slowly but they are not unchanging; even experts underestimate global vaccination rates; when bad things happen it's usually not because people intend them to; and small steps usually work better than drastic action.

Underlying these Factfulness rules of thumb are critical thinking, logic, and the courage to express oneself in tense situations -- as reflected by the tale of the Congolese woman who saved Hans Rosling from a mob of angry men with machetes, told in Chapter Eleven. This chapter also gives more advice on how to incorporate Factfulness into one's daily life.

- When it comes to education, we need to teach our children a combination of critical thinking skills, an up-to-date fact-based framework (e.g. life on the four levels), and humility and curiosity. (Recall that curiosity and humility are both on Yudkowsky's list of Twelve Virtues.)

- In business, it is more important than ever to know about the world. The fastest-growing future markets will be in Africa and Asia, not Europe or the U.S.. Global businesses need international employees, so tone down the American or European branding. Don't be afraid to invest in African countries like Ghana or Kenya, as they will likely inherit the textiles industry from Cambodia and Bangladesh.

- If you are a journalist, activist or politician, you should regularly update your worldview, set numbers in their historical context, and try to communicate more constructive news. But given the nature of media, it is somewhat understandable if news outlets never present the world neutrally and non-dramatically. It is up to consumers to consume the news more factfully.

- In your local community or organization, there are probably also facts that are systematically ignored. Do you know the proportion of people in your own country that will be older than 65 in ten years? Do your colleagues know the basic facts about your area of expertise? Ask!

"Hans's dream of a fact-based worldview lives on in us and, we hope now, in you too." (p. 259)

***

I think that Factfulness fits nicely onto a Rationalist's bookshelf, especially since it is explicitly about being less wrong about the world (at least regarding international health). There is the question of whether someone already familiar with the Effective Altruism community or Hans Rosling's TED Talks will gain new insight from the book; I think they likely will, at least based on my experience. The Gapminder fact questions, the "four income levels", the photographs from Dollar Street, and many of the facts and trends in the book were new to me.

That being said, the reader might also recognize links to existing work in psychology and behavioral economics, such as scope insensitivity (the size instinct), scarcity (the urgency instinct), availability bias (the fear instinct), or loss aversion (the negativity instinct). Chapter Eight is reminiscent of Eliezer Yudkowsky's concept of the happy death spiral, such as when Rosling writes:

"And it is easy to take off down a slippery slope, from one attention-grabbing simple idea to a feeling that this idea beautifully explains, or is the beautiful solution for, lots of other things. The world becomes simple." (p. 186)Many parts of Factfulness remind one of Nassim Taleb's idea of the narrative fallacy, and sometimes even the idea that the news can make you worse at understanding the world. When Rosling writes about how even investment bankers, elites at the World Economic Forum, and Nobel laureates get the fact questions wrong, there is a hint of Taleb's expert problem about it.

What the Rosling family is skilled at doing, though, is presenting all these concepts in a very accessible, clear and engaging way. Therefore it is also great for readers who aren't acquainted with the EA or rationality spheres. (There are some folks though, like political radicals, anti-vaxxers, and proponents of so-called "human biodiversity", who may get annoyed at this book.)

Factfulness was written for a popular audience, yet it doesn't compromise on the notes and references. They even have a website with a list of mistakes -- which indicates that they really are concerned about accuracy and transparency. The main concern I'd have with a book like this, is that it may not age well if the facts change over the coming decades. On the other hand, many of the principles (e.g. most things improve) should be timeless.

Overall, I would recommend everyone to read it, and suggest every school library to get a copy.

Comments

Post a Comment