Thriving on Entropy

Book Review:

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, "Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder", Penguin Books, 2013.

In his book Adapt, Tim Harford argues that we should be experimenting with multiple projects in parallel since not all of them will pay off, but when an experiment is successful, it can transform our lives for the better "in a way that a failed experiment will not transform them for the worse". This asymmetry lies at the heart of Nassim Nicholas Taleb's book Antifragile, which promotes the idea of antifragile tinkering or bricolage -- a kind of trial-and-error in which small mistakes are good and one wishes to "fail fast", because this gives one the option to keep a hugely favorable result while limiting the bad, as long as one has the rationality to identify and exploit large gains.

(Incidentally, Taleb wrote a review for Harford's Adapt with rare praise: "Adapt is a highly readable, even entertaining, argument against top-down design. It debunks the Soviet-Harvard command-and-control style of planning and approach to economic policies and regulations, and vindicates trial-and-error (particularly the error part in it) as a means to economic and general progress. Very impressive!")

Written after The Black Swan and the first edition of The Bed of Procrustes, Nassim N. Taleb considers Antifragile to be his "central work". Whereas his previous books (see my reviews of Fooled by Randomness, The Black Swan, and The Bed of Procrustes) were written "to convince us of a dire situation" (p. 14), Antifragile takes for granted that history and society are dominated by Black Swan events and nonlinearities, and hence that we don't quite understand the world. Thus, the book jumps right into a practical and prescriptive treatment. So, what is the core idea of "antifragility"? As the author explains in the Prologue:

"Wind extinguishes a candle and energizes fire. Likewise with randomness, uncertainty, chaos: you want to use them, not hide from them. You want to be the fire and wish for the wind. [...] Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile." (p. 3)As Taleb emphasizes, the opposite of fragility is not robustness or resilience! To be specific, something is "robust" when it resists shocks, stays the same, and is generally "safe". But for Taleb, robustness is not good enough to be an antidote to the Black Swan problem -- we don't just want to survive; we want to get better and, as the subtitle of the book suggests, gain from disorder. The mission is to conquer uncertainty and opacity, not by trying to predict things, but by doing things well despite not understanding them. This means looking for things that have more upside than downside from random events, taking inspiration from Mother Nature (since it has survived for billions of years), practicing trial and error, and not interfering with complex systems.

In the rest of the Prologue, Taleb explains the notion of the fragilista: someone who assumes that the reasons behind things are always accessible and who overestimates the reach of scientific knowledge, consequently advocating for policies that have small and visible benefits, but hidden severe side-effects. In other words, he or she contributes to fragility by trying to reduce variability and errors in systems that love variability and errors (e.g. organisms, cultures, cuisines, political and legal systems, cities, economies, and technological innovations). Without occasional stressors, Taleb argues, these systems will weaken or "blow up". Unfortunately, the modern world is increasingly complicated and therefore vulnerable to Black Swans, because certain people (who fall for the "Soviet-Harvard delusion", Taleb's nickname for naive rationalism) insist on top-down intervention and resist the natural, ancestral and simple. This is related to the concept of iatrogenics (harm caused by the healer) introduced in the Postscript of The Black Swan.

I think Taleb is half-kidding when he says that fragilistas are usually wearing suit and tie, sitting in meetings or at desks studying newspapers, using PowerPoint in conferences they fly to, name-dropping, and lacking a sense of humor. But he seems serious when talking about the ethics of what they do, which is to game the system by transferring the gains of antifragility to themselves while leaving others to bear the costs of fragility. In other words, they have no "skin in the game" (which also happens to be the title of Taleb's latest book). Whereas Taleb, as a practitioner, claims to eat his own cooking, he accuses some others of lacking doxastic commitment (i.e. having nothing to lose by being wrong). Taleb's ethical rule is: "If you see fraud and do not say fraud, you are a fraud" (p. 15). Thus, as we shall see later on, he names the "Robert Rubin problem", the "Joseph Stiglitz problem" and the "Alan Blinder problem".

The rest of Antifragile is divided into seven "books" (which are really parts or sections) plus an extensive notes section (comprising the glossary, two appendices of graphs and technical notes, further readings, and the bibliography and index). In total, the whole thing spans over 500 pages, probably making it Taleb's lengthiest published book so far. There is also technical backup material on the author's website. I shall try to summarize Antifragile here without the post getting too long.

***

Before the first chapter, N.N. Taleb presents to us a table summarizing The Triad, the spectrum of fragile -- robust -- antifragile. The idea is simply to move from the fragile toward the antifragile, insofar it is possible. This solution can be applied in a diverse range of areas, from politics and economics to philosophy, scientific discovery and even medicine. Of course, a disclaimer: antifragility is a relative term, and works only up to a certain level of stress.

FRAGILE: Large, exposed to negative Black Swans, hates mistakes, errors are rare but large, concentrated sources of randomness, model-based probabilistic decision making, directed research, explicit knowledge, theory, academia, classroom learning, soccer moms, modernity, tourists, rationalism, True-False epistemology, Plato and Aristotle, regulation via rules, statutory law, post-agricultural modern settlements, the centralized nation-state, the New York banking system, bureaucrats, industry, food companies, debt, corporate employment, middle class, chronic stressors, atrophy, aging, post-traumatic stress, and via positiva medicine (adding medication).

ROBUST: Small but specialized, mistakes are just information, heuristics-based decision making, opportunistic research, tacit knowledge, phenomenology, expertise, learning through real life/street life, Medieval European philosophy, empiricism, Popper and Wittgenstein, regulation via principles, small business, equity financing, dentists, minimum-wage earners, Mithridatization, and recovery.

ANTIFRAGILE: Small but not specialized, exposed to positive Black Swans, loves mistakes, errors are small and reversible, distributed sources of randomness, decision making with convex heuristics, stochastic tinkering ("bricolage"), tacit knowledge with convexity, evidence-based phenomenology, heuristics and practical tricks, erudition, learning through real life and library, barbell education (parental library plus street fights), Ancient Mediterranean philosophy, flâneurs, skeptical empiricism, Sucker-Nonsucker epistemology, Roman Stoics and Nietzsche, regulation via virtue, common law, nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes, a decentralized collection of city-states, Silicon Valley ("fail fast"), entrepreneurs, artisans, restaurants, venture capital, taxi drivers and prostitutes, Bohemian aristocracy, acute stressors with recovery, hormesis, hypertrophy, post-traumatic growth, and via negativa medicine (removing harmful items from consumption).

***

Names of the "books": The Antifragile: An Introduction -- Modernity and the Denial of Antifragility -- A Nonpredictive View of the World -- Optionality, Technology, and the Intelligence of Antifragility -- The Nonlinear and the Nonlinear -- Via Negativa -- The Ethics of Fragility and Antifragility

An antifragile system

- The first chapter in Antifragile opens with an amusing picture: the opposite of a fragile package would have "please mishandle" stamped on it! Nassim Nicholas Taleb spends the chapter reiterating that the robust and resilient are neutral in the sense that they neither break nor improve from shocks, whereas the antifragile is like the fragile with a negative sign in front. There is no common word for this idea, which is why Taleb had to coin it. However, ancient mythology features stories like the sword of Damocles (fragility) and Hydra (antifragility), showing that we have the intuition for it. Pharmacologists and toxicologists talk about hormesis when a small dose of a poisonous substance actually makes you better off. Unfortunately, people struggle to transfer the concept to different domains.

- Antifragility manifests in the overcompensation to stressors -- whether in psychology (see post-traumatic growth) or the economy. Taleb asserts that most innovation comes from technicians and entrepreneurs, not from bureaucratic planning or Harvard professors. Challenge and setbacks (up to a point) seem to bring out the best in people by motivating them, and helping them prepare for even worse. Taleb gives more examples: weightlifting, antibiotic resistance, and books/ideas (which get "nourished" by attacks -- this reminds me of the Streisand effect). Because it's hard to control one's reputation, certain jobs are more vulnerable to harm from criticism: mid-level bank employees and civil servants more so, taxi drivers and artists less so.

- Taleb argues that antifragility is a key characteristic of living systems -- inanimate objects typically do not self-repair after stress, while your body does (up to a point). In fact, an absence of low-level stressors might contribute to the symptoms associated with aging (e.g. bone and muscle degeneration). Taleb concedes that we eventually die due to senescence, which he says "might not be avoidable, and should not be avoided" (p. 55), but I find the argumentation weak on this point. His more interesting point is that complex systems (e.g. cultures and markets) are closer to the organic than the mechanical; so they are antifragile for similar reasons. Here he disagrees with the notion that the economy is like a machine that needs maintenance (as expressed, for example, in The Undercover Economist Strikes Back). By trying to suck all the randomness and variability out of life, we fall prey to touristification (i.e. the tyranny of precise and rigid plans). We should instead be flâneurs: revising our schedules at every step.

- Elaborating on organisms, Chapter 4 introduces the idea that the antifragility of the whole often comes from the fragility of its parts. The failure of individual startups benefits the economy; the death of biological organisms allows for evolution through the survival of genetic information (see also my articles "Immortal Cooperation" and "A Gene's Eye View of History"). Nature does not need to predict the future to survive -- it just modifies the population each generation. In a somewhat related way, the tragedies of plane crashes and nuclear reactor meltdowns give us useful information, so we can make these systems safer. But when governments bail out bankrupt businesses, they undermine the collective. Taleb concludes this section by praising heroic entrepreneurs who take personal risks for the sake of the planet's growth.

|

| An illustration of the difference between Mediocristan and Extremistan (p. 91). |

|

| From Appendix I: A Graphical Tour of the Book. How antifragility differs from robustness (p. 436). |

Healed by the nation-state?

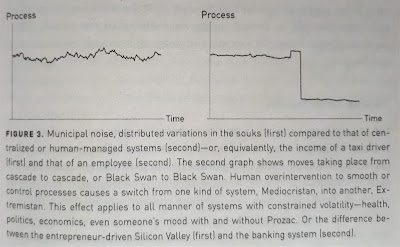

The second section of Antifragile explores the ways in which we harm our social, political and economic systems by trying to fit them into a Procrustean bed (named after the mythic Greek inn-keeper Procrustes, who got travelers to fit into his bed perfectly by either cutting or stretching their limbs). Often, this is by simplifying the nonlinear to the linear.- It may seem at first glance that the variability of the incomes of taxi drivers, prostitutes, tailors and other artisans would be undesirable, but these careers are actually less likely to suffer from unemployment with zero income compared to bank employees, and more likely to experience positive surprises. Likewise, the centralized state gives the illusion of being smooth and steady, but is ultimately fragile. Taleb uses Switzerland as an example of the success of small, municipal government.

- Chapter 6 provides more examples of how some variability can be beneficial. Without the mild volatility caused by speculators, the markets get used to periods of calm during which hidden risks accumulate, culminating in a large crisis when there is the slightest panic. Without occasional small forest fires, flammable material will accumulate. Computer scientists use simulated annealing (see here) to solve problems by injecting randomness. Perhaps most controversially, Taleb claims that in absence of small wars, countries become more vulnerable to Black Swan blowups.

- A key feature of modernity, according to Taleb, is naive interventionism: the instinct that doing something is always better than nothing. The problem is that sometimes, the costs of treatment (whether medicine or public policy) are greater than the benefits. This harm is called iatrogenics, and it is worsened by the agency problem (in which some "expert" manager, stock broker, politician or academic takes hidden risks for their own benefit, without paying the price when they're wrong). Not all intervention is bad -- we must act to avoid "blowing up the planet and ourselves" (p. 121) as Taleb puts it.

- Another element of modernity is faith in scientific prediction, and political and economic turmoil is often blamed on poor forecasting. This angers Taleb because, not only are significant rare events in Extremistan unpredictable, making predictions causes people to take more risk (it has iatrogenics). The solution is simple: become more robust or antifragile to events such as wars, earthquakes, financial crises, epidemics etc. -- by focusing on exposure (not probabilities) and utilizing redundancy.

|

| An illustration of how more intervention doesn't always help (p. 435). The graph can also depict hormesis for an organism. |

|

| The barbell strategy of combining extremely safe with extremely speculative bets (p. 438). |

Fat Tonyism as antifragility

- In Chapter 9, the character Fat Tony from Brooklyn returns, along with his friend Nero Tulip. While Nero spends a lot of time alone with books, Fat Tony is gregarious and mostly alternates between restaurants and spas. Despite their differences, both men profited from the 2008 economic crisis because they anticipated that suckers would go bust due to fragilities.

- Fat Tony's intuitions are related to the writings of Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca. A wealthy man, Seneca practiced what he preached about being indifferent to fate (he even took his own life when ordered to do so). Moreover, Seneca wanted to keep the upside of life while mitigating the downside -- this is the favorable asymmetry that is characteristic of antifragility.

- How can we implement Seneca's fundamental asymmetry to gain more than we lose from randomness, volatility, uncertainty, errors, stressors, and time? Well, the barbell strategy says to avoid a "monomodal" approach (putting all your eggs in one basket). Instead, a bimodal strategy would be like marrying an accountant (safe) and occasionally cheating with a rock star (risky). Or, put 90% of your money in a savings account and 10% in speculative securities. This limits your loss, which is not the case when you put 100% in "medium" risk activities.

Against the Soviet-Harvard illusion

The teleological fallacy, according to N.N. Taleb, is the mistake of thinking that "you know exactly where you are going" (p. 170) and that this is how you will succeed. (Incidentally, Eliezer Yudkowsky has also written about teleology.) Of course, this is related to touristification -- and it is not the source of innovation.- The story of Thales of Miletus shows that it is not knowledge but optionality (i.e. having the option to change one's course like a rational flâneur) that yields success. Thales cheaply rented all the olive presses in his region, and profited when there was a bountiful harvest. He didn't know what the crop would be; he just exploited the asymmetry between a limited loss and unlimited gains.

- Taleb begins Chapter 13 by asking why it took so long after the invention of the wheel for someone to put tiny wheels under suitcases. He argues that discoveries come mostly through chance, and that we tend to detect options through practice (trial and error). Governments and universities don't produce academic knowledge that leads to practical technologies and wealth; rather, antifragile tinkering produces technology, practice and wealth, which then lead to academic theories and education. Yet, the Soviet-Harvard priests will claim credit: Taleb calls this the lecturing-birds-how-to-fly effect.

- Education may be valuable for a number of reasons, but GDP growth isn't one. Some folks assume that a certain piece of narrative knowledge is necessary to be successful, when the more relevant source is less visible and more tinkering-based. They fall for the green lumber fallacy, so called because a commodity trader does not need to know that "green lumber" is fresh (as opposed to painted) in order to be a successful trader. The problem with trying to translate theory into practice is that an idea is not the "same thing" as the real profits made from it.

- Examples of results that originally came from engineers, businesses, hobbyists and other practitioners but were misattributed to academia include: the jet engine, architecture, cybernetics, derivatives formulas, medicines, the Industrial Revolution, and other technologies. Taleb is not arguing against science -- just against unconditional belief in organized science and pseudoscience.

- In Chapter 16, the author complains about soccer moms and how they raise children to be nerds, rather than exposing them to ecological ambiguity. A better kind of education would emphasize money and culture instead of grades, autodidacticism instead of standardized learning, and curiosity instead of concentration.

- The great Socrates fell for the green lumber fallacy when he challenged Euthyphro to define "piety". Taleb uses the character Fat Tony to argue that we don't need to be able to define a word in order to act. He also cites Nietzsche's point that what is unintelligible is not necessarily unintelligent. There is a distinction between the Apollonian (balanced and rational) and the Dionysian (untamed and impenetrable), and we need both.

Nassim Taleb and the Philosopher's Stone

Here, in what is the "plumbing of the book" (Taleb's words, p. 19), we get acquainted with a way to analyze the nonlinear. It is, in essence, an extension of Seneca's fundamental asymmetry.- Would you rather get hit by a thousand small pebbles, or one large stone that weighs as much as the pebbles combined? You'd probably choose the pebbles, because fragility is nonlinear: twice the mass does more than twice the harm. Conversely, lifting 50 kg once is (presumably) more beneficial than lifting 25 kg twice. These convexity effects (shown in the graphs above) are everywhere: the effect of the number of cars on traffic time, the effect of a corporation's size on the costs when it gets squeezed, and the effect of pollution on ecological harm.

- Like alchemists turning lead into gold, the philosopher's stone (Taleb's nickname for convexity bias) allows us to get results without much intelligence. It is based on Jensen's inequality, which basically says that a convex function of the expectation of variable x is always less than or equal to the expectation of the function of x (although Taleb doesn't explain this well). For example, if you square the average of a six-sided die (3.5) you get 12.25 but if you average the squares you get approximately 15.17. The difference is what Taleb considers the benefit of optionality. The inverse philosopher's stone is the opposite: for example, your grandmother's health is better at f(average of -17 and 60 Celsius) than at the average of f(-17) and f(60).

|

| The probability distribution of harms and benefits from treatment, showing how potential (hidden and delayed) costs are larger than the visible yet mild benefits (p. 442). |

|

| When someone is seriously ill, and treatment is potentially lifesaving, risky medical intervention is justified due to positive convexity, i.e. the "barbell effect" (p. 443). |

To commit or to omit?

Next, Nassim Nicholas Taleb explores the tendency of time to break the fragile, and more specifically, what convexity effects imply for medicine. The focus is on via negativa: a subtractive rather than additive approach to risk management. In other words, it's about what we shouldn't do rather than what we should; what is wrong rather than what is right; and what something isn't rather than what it is. This ties back to the earlier chapters on naive interventionism and iatrogenics.- In Fooled by Randomness, Taleb wrote that "age is beauty". In Chapter 20 of Antifragile, the author again argues that "the old is superior to the new, and much more than you think" (p. 309). This is due to the Lindy effect: the "old" has a longer life expectancy than the "young" in proportion to their age, since the longer something (e.g. a technology or book, but alas not a human) has survived, the longer it can be expected to survive. Our society, however, suffers from what Taleb calls neomania, the love of new stuff for the sake of it. A subtractive prophecy would warn us that vulnerable things (e.g. the large) will break. Meanwhile the age-old will continue to stick around like Empedocles' Tile, a natural friend to the dog who always sleeps on that same tile (for reasons we may or may not understand).

- Taleb's approach to medical decision-making is one of risk management: since "no evidence of harm" is not the same as "evidence of no harm", the modern and non-natural carries the burden of proof. Says the author: "It seemed to me that it was an insult to Mother Nature to override her programmed reactions unless we had a good reason to do so..." (p. 338). He argues that we should follow via negativa -- removing harmful things (e.g. cigarettes, trans fats, thalidomide, steroids) rather than popping pills, sucker-style.

- While life expectancy has increased, we should attribute it to things like sanitation, penicillin, and life-saving surgeries, not all medical treatments. Overtreatment, in fact, shortens life expectancy. If you want to live longer, Taleb suggests caloric restriction (occasional fasting), a "Paleo" diet (with episodes of veganism), and avoiding things that make you explosively angry. Again, these are examples of via negativa. But Taleb rejects the idea of trying to live forever -- he feels like we morally ought to die honorably/heroically for the sake of the collective, since the fragility of the individual makes for the antifragility of the system. Only through your information (e.g. genes or books) should you seek immortality. Needless to say, transhumanists will disagree with this point.

Prelude to Skin in the Game

The final "book" of Antifragile discusses the ethics of transferring the harms of fragility to another party while keeping the benefits for oneself. The complexity of the modern world makes it easier to hide iatrogenics, which is why Taleb advocates for simple heuristics like skin in the game (also known as the Captain and Ship Rule, which says that the captain must go down with his ship).- When people lack the courage to make sacrifices, agency problems arise. Here, Taleb identifies those without skin in the game as owning hidden options at others' expense, and this category includes bureaucrats, consultants, data miners, editors, and journalists who predict. By contrast, people with skin in the game (who keep their own downside risk) include citizens, merchants, lab experimenters, writers, and traders. Finally, in the style of the Triad, there are also those who take the harm on behalf of and for the sake of others -- these soldiers, prophets, maverick scientists, great writers, and journalists who take risks to expose frauds, are said to have "soul in the game". In the rest of Chapter 23, we read about Hammurabi's code, a 3,800-year-old rule that says a builder shall be put to death if the house he built collapses and kills the owner. This relates to doxastic commitment (an aspect of soul in the game), the idea that people should have something to lose by being wrong in their belief, opinion or prediction. When people just talk, they are tempted by cherry-picking (selecting only data that proves their point), an example of which is the Joseph Stiglitz problem. The economist Stiglitz, perhaps unwittingly, contributed to the 2007-2008 crisis by publishing papers saying that Fannie Mae would not go bust; then later on claimed to have "predicted" the crisis (the ex post cherry-picking). Of course, Stiglitz faced no penalty. Related syndromes include the Robert Rubin problem (a Citibank executive who kept his millions in bonuses when the bank had to be bailed out by taxpayers) and the Alan Blinder problem (an economist and former regulator who proposed a legal yet unethical mechanism for investors to get all their deposits insured for free by the government i.e. taxpayer). Taleb considers these free options ethical violations.

- The antidote to the Stiglitz syndrome is not to listen to what people say, but to look at what they do (as Taleb quips: "Never listen to a leftist who does not give away his fortune or does not live the exact lifestyle he wants others to follow" (pp. 395-396)). But another solution, discussed in Chapter 24, is to choose one's profession according to one's ethics and beliefs, rather than the other way around. Today there is a tantalized class of tie-wearing, wealth-chasing people (e.g. bureaucrats, lobbyist, bankers) stuck on a treadmill, who can be bribed given the right narrative. Others vulnerable to opportunistic pseudoethics (or ethical inversion) include gold-diggers, networkers, and academic researchers. By contrast, prostitutes, social persons and independent scholars are more likely to fit their actions to their beliefs, and are more credible since they may have opinions that go against their own interest. In a sense, they also have more freedom. Taleb himself refuses to teach standard risk methods that he believes are nonsense (e.g. Markowitz-style portfolio theory), but sadly many economics professors continue to teach these because "that's what everybody is doing" and that's how they get a job. According to Taleb, they are wimps.

"The best way to verify that you are alive is by checking if you like variations. Remember that food would not have a taste if it weren't for hunger; results are meaningless without effort, joy without sadness, convictions without uncertainty, and an ethical life isn't so when stripped of personal risks." (p. 423)

In the Epilogue, the character Fat Tony dies from an aortic aneurysm. Nero receives a share of the estate, to be spent on a noble yet secret mission.

So, there you have a summary of this epic book. Antifragile is a worthy successor to The Black Swan, and has similar characteristics: it is, for the most part, written clearly; it displays a wry sense of humor (which some readers interpret as smugness); and incorporates fictional vignettes. The chapters are prefaced with cryptic summaries (e.g. for Chapter 2: "Is it easy to write on a Heathrow runway? - Try to get the Pope to ban your work - How to beat up an economist (but not too hard, just enough to go to jail)"), and the headings can be opaque too (e.g. "Plus or Minus Bad Teeth" in Chapter 8). The book is livened up by tables, graphs and drawings. As with The Black Swan and Fooled by Randomness before it, Taleb likes to quote Yogi Berra:

The concept of antifragility offers some interesting angles on free-market economics. For example, on page 114 the author writes: "Perhaps the idea behind capitalism is an inverse-iatrogenic effect, the unintended-but-not-so-unintended consequences: the system facilitates the conversion of selfish aims [...] at the individual level into beneficial results for the collective." To put it another way, capitalism helps to "greed-proof" society much better than rationalistic utopianism can (pp. 136-137). In this view, what matters isn't prediction but survival -- similar to how evolution works in Mother Nature. As Taleb says:

In the context of psychology, Taleb promotes the work of Dan Goldstein and Gerd Gigerenzer, who argued that "fast and frugal" heuristics can work better than complicated methods. Eliezer Yudkowsky has mixed feelings toward this body of literature, suggesting that on the one hand, they "make a few too many lemons into lemonade", yet on the other hand, they have "the most psychologically realistic models of any school of decision theory". I feel like I'll have to read more about this school of thought, but for now it is interesting to note some frictions with the traditional heuristics-and-biases approach. For instance, Nassim Taleb rejects the idea that procrastination is always bad, as it can be seen as a "naturalistic filter" (p. 122) against over-intervention. Put more aggressively:

Of course, as we have seen, Taleb maintains that he is not against science, just scientism. His main concern is with "how not to be a turkey", which is made easier by avoiding manufactured stability that gives a false sense of safety. This was the key point in The Black Swan, but Antifragile takes it a step further by introducing the inverse turkey, someone who fails to see opportunities and who underestimates the large (yet rare) benefits of antifragility. Being a rational flâneur is meant to avoid both errors. The flâneur will take non-narrative action (or follow a robust narrative which does not change its recommendations when the assumptions change). Unfortunately much of social science today is a narrative discipline in which data mining and cherry-picking is used to fit a good-sounding story to the past. In fact, as Taleb writes in the Notes section, any statistical method using "squares" (e.g. regression, standard deviation, correlation, covariance matrices, etc., common in economics and epidemiology) is unreliable in fat-tailed domains. Thus, in order to be a non-sucker, you sometimes need to rely on opaque heuristics -- practical rules of thumb that have been around for a long time, even though they seem not to make sense. One such heuristic, for instance, is that less is more. Hence all the talk about iatrogenics. The point is that rationality may sometimes ask you to diverge from the scientific establishment; a point that Yudkowsky explains at length in his sequence "Science and Rationality". (You can read my summary here.)

While Nassim Taleb is somewhat of an iconoclast, he is not entirely alone. For example, Robin Hanson has suggested that the U.S. spends too much on medicine for what it empirically delivers. Bryan Caplan wrote a whole book challenging academic education. The idea of the Lindy effect (which Taleb got from Mandelbrot) has been picked up by, among others, Christian and Griffiths in their book Algorithms to Live By (although they refer to it as the Copernican Principle and never cite Taleb). And there are many who agree with him on the ethics of bankers.

Taleb has been variously referred to as "a radical philosopher for our times" and "an uncompromizing [sic] no-nonsense thinker for our times" by Penguin Books. He is a "man of letters" (literary essayist), a businessman/trader, and university professor. These descriptions will ring true when you read Antifragile -- a book that celebrates poetry, commerce, and independent scholarship, while calling out BS from all walks of life. I gave it 5/5 stars on Goodreads, as I can recommend it to everyone as a book that, whether you end up agreeing with it or not, can enrich one's outlook on life.

Here is my collection of the Penguin paperbacks of the Incerto. As for the latest volume, Skin in the Game, I might wait until its second edition is published.

***

So, there you have a summary of this epic book. Antifragile is a worthy successor to The Black Swan, and has similar characteristics: it is, for the most part, written clearly; it displays a wry sense of humor (which some readers interpret as smugness); and incorporates fictional vignettes. The chapters are prefaced with cryptic summaries (e.g. for Chapter 2: "Is it easy to write on a Heathrow runway? - Try to get the Pope to ban your work - How to beat up an economist (but not too hard, just enough to go to jail)"), and the headings can be opaque too (e.g. "Plus or Minus Bad Teeth" in Chapter 8). The book is livened up by tables, graphs and drawings. As with The Black Swan and Fooled by Randomness before it, Taleb likes to quote Yogi Berra:

- "We made the wrong mistake" (p. 85)

- "In theory there is no difference between theory and practice; in practice there is" (p. 213)

The concept of antifragility offers some interesting angles on free-market economics. For example, on page 114 the author writes: "Perhaps the idea behind capitalism is an inverse-iatrogenic effect, the unintended-but-not-so-unintended consequences: the system facilitates the conversion of selfish aims [...] at the individual level into beneficial results for the collective." To put it another way, capitalism helps to "greed-proof" society much better than rationalistic utopianism can (pp. 136-137). In this view, what matters isn't prediction but survival -- similar to how evolution works in Mother Nature. As Taleb says:

"It appears to be the most underestimated argument in favor of free enterprise and a society driven by individual doers, what Adam Smith called "adventurers," not central planners and bureaucratic apparatuses. [...] institutions mess things up, as suckers may get bigger -- institutions block evolution with bailouts and statism." (p. 391)Similar sentiments are expressed in The Black Swan. Note also the connection to Tim Harford's Adapt, which compares the market to natural selection, emphasizing the bottom-up trial-and-error approach.

In the context of psychology, Taleb promotes the work of Dan Goldstein and Gerd Gigerenzer, who argued that "fast and frugal" heuristics can work better than complicated methods. Eliezer Yudkowsky has mixed feelings toward this body of literature, suggesting that on the one hand, they "make a few too many lemons into lemonade", yet on the other hand, they have "the most psychologically realistic models of any school of decision theory". I feel like I'll have to read more about this school of thought, but for now it is interesting to note some frictions with the traditional heuristics-and-biases approach. For instance, Nassim Taleb rejects the idea that procrastination is always bad, as it can be seen as a "naturalistic filter" (p. 122) against over-intervention. Put more aggressively:

"Using my ecological reasoning, someone who procrastinates is not irrational; it is his environment that is irrational. And the psychologist or economist calling him irrational is the one who is beyond irrational." (p. 123)Taleb also dislikes the ideas of "social engineers" and "nudge manipulators", likening them to touristification (removing the messy uncertainty from life). Incidentally, I shall review the book Nudge here soon, where I'll report whether I find it a fair critique. Perhaps a more concerning attack on psychology is when Taleb writes that psychiatric medication (such as for ADHD or depression) may be doing more harm than good to children. It is one thing to decry overmedication (a valid point), but Taleb goes so far as to call such diseases "imagined or invented" (p. 112).

Of course, as we have seen, Taleb maintains that he is not against science, just scientism. His main concern is with "how not to be a turkey", which is made easier by avoiding manufactured stability that gives a false sense of safety. This was the key point in The Black Swan, but Antifragile takes it a step further by introducing the inverse turkey, someone who fails to see opportunities and who underestimates the large (yet rare) benefits of antifragility. Being a rational flâneur is meant to avoid both errors. The flâneur will take non-narrative action (or follow a robust narrative which does not change its recommendations when the assumptions change). Unfortunately much of social science today is a narrative discipline in which data mining and cherry-picking is used to fit a good-sounding story to the past. In fact, as Taleb writes in the Notes section, any statistical method using "squares" (e.g. regression, standard deviation, correlation, covariance matrices, etc., common in economics and epidemiology) is unreliable in fat-tailed domains. Thus, in order to be a non-sucker, you sometimes need to rely on opaque heuristics -- practical rules of thumb that have been around for a long time, even though they seem not to make sense. One such heuristic, for instance, is that less is more. Hence all the talk about iatrogenics. The point is that rationality may sometimes ask you to diverge from the scientific establishment; a point that Yudkowsky explains at length in his sequence "Science and Rationality". (You can read my summary here.)

While Nassim Taleb is somewhat of an iconoclast, he is not entirely alone. For example, Robin Hanson has suggested that the U.S. spends too much on medicine for what it empirically delivers. Bryan Caplan wrote a whole book challenging academic education. The idea of the Lindy effect (which Taleb got from Mandelbrot) has been picked up by, among others, Christian and Griffiths in their book Algorithms to Live By (although they refer to it as the Copernican Principle and never cite Taleb). And there are many who agree with him on the ethics of bankers.

Taleb has been variously referred to as "a radical philosopher for our times" and "an uncompromizing [sic] no-nonsense thinker for our times" by Penguin Books. He is a "man of letters" (literary essayist), a businessman/trader, and university professor. These descriptions will ring true when you read Antifragile -- a book that celebrates poetry, commerce, and independent scholarship, while calling out BS from all walks of life. I gave it 5/5 stars on Goodreads, as I can recommend it to everyone as a book that, whether you end up agreeing with it or not, can enrich one's outlook on life.

***

Here is my collection of the Penguin paperbacks of the Incerto. As for the latest volume, Skin in the Game, I might wait until its second edition is published.

Comments

Post a Comment