Intelligent Design

Book Review:

Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, "Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness", Penguin Books, 2009.

Just over a decade ago, a book by the title Nudge took the world by storm. Today, there are numerous "nudge units" sponsored by governments (the most famous of which is the Behavioural Insights Team), and one of the co-authors, Richard H. Thaler, won the 2017 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. Nudge is also listed on the Hufflepuff rationality bookshelf. Given the status of the book, it's odd that I haven't read it earlier. But now I have, and below are my notes.

Nudge begins by asking how the director of food services for a city's school system should tell the cafeterias to arrange and display the food choices, knowing that (a) people, including kids, are influenced by small changes in context, such as the order of items, and (b) there's no way to avoid organizing the food. The authors, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, argue that the choice architect should arrange the food "to make the students best off, all things considered" (p. 2). This may seem a bit paternalistic, but it's better than the alternatives of arranging things randomly (which leaves some children with less healthy diets than others) or maximizing the profits of the suppliers. In fact, the authors call their philosophy libertarian paternalism: libertarian because we can influence others in ways that still preserve their freedom of choice; and paternalism because the goal is to improve people's lives, such that people will agree that they are better off. In other words, it's a soft kind of paternalism that avoids mandates or bans. A nudge is then defined as:

A good summary of the book is provided by the authors near the end:

Speaking of human biases and blunders, Part I of Nudge discusses the social science research of the past four (or five) decades, with which you may already be quite familiar if you hang around in the Rationality or self-improvement spheres. Nevertheless, I'll do a perfunctory summary.

Nudge begins by asking how the director of food services for a city's school system should tell the cafeterias to arrange and display the food choices, knowing that (a) people, including kids, are influenced by small changes in context, such as the order of items, and (b) there's no way to avoid organizing the food. The authors, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, argue that the choice architect should arrange the food "to make the students best off, all things considered" (p. 2). This may seem a bit paternalistic, but it's better than the alternatives of arranging things randomly (which leaves some children with less healthy diets than others) or maximizing the profits of the suppliers. In fact, the authors call their philosophy libertarian paternalism: libertarian because we can influence others in ways that still preserve their freedom of choice; and paternalism because the goal is to improve people's lives, such that people will agree that they are better off. In other words, it's a soft kind of paternalism that avoids mandates or bans. A nudge is then defined as:

"... any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives." (p. 6)The opportunity for nudging comes from the fact that people often make bad decisions due to incomplete information, fallible memories, limited self-control and attention spans, laziness, and other predictable biases. People's choices aren't always optimal, but given that those choices are influenced by design elements, we might as well gently nudge people toward better choices. Libertarian paternalism can be applied in the private sphere and the public sphere, and the authors hope that their recommendations will be welcomed by both sides of the political spectrum, since the costs tend to be very low and people's options aren't eliminated.

A good summary of the book is provided by the authors near the end:

"In this book we have made two major claims. The first is that seemingly small features of social situations can have massive effects on people's behavior; nudges are everywhere, even if we do not see them. Choice architecture, both good and bad, is pervasive and unavoidable, and it greatly affects our decisions. The second claim is that libertarian paternalism is not an oxymoron. Choice architects can preserve freedom of choice while also nudging people in directions that will improve their lives." (p. 253)I think both claims have merit, but on the first one I'm not sure how massive the effects really are. For now, let's see why Thaler and Sunstein think that choice architecture is unavoidable. From Chapter 15:

"Often life turns up problems that people did not anticipate -- for investments, rental car and credit card agreements, mortgages, and uses of energy. Both private and public institutions need rules to determine how such situations are handled. When those rules seem invisible, it is because people find them so obvious and so sensible that they do not see them as rules at all. But the rules are nonetheless there, and sometimes they are not so sensible." (p. 237)This is an underappreciated point, I think; yet it clashes somewhat with Nassim N. Taleb's warning that age-old societal practices that seem irrational on the surface may actually have good reasons for sticking around (even if those reasons are opaque), or with the idea of Chesterton's Fence. In fact, Thaler and Sunstein acknowledge in a footnote that the argument made by Edmund Burke for long-standing traditions may be sensible, but they reiterate that some social practices only persist due to inertia, procrastination and imitation.

Speaking of human biases and blunders, Part I of Nudge discusses the social science research of the past four (or five) decades, with which you may already be quite familiar if you hang around in the Rationality or self-improvement spheres. Nevertheless, I'll do a perfunctory summary.

***

The behavioral foundations

Thaler and Sunstein build on the work of psychologists like Kahneman, Tversky, Gilovich, Nisbett, Cialdini, Loewenstein (a behavioral economist) and others who showed how humans are not like the homo economicus of textbook economics. Among the many predictable errors we make are: (i) using biased heuristics due to bounded rationality; (ii) giving in to temptations due to poor self-control; and (iii) following the crowd due to social influences. These are addressed in chapters 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

- Many of our judgments are automatic, with little effortful reflection. We often use rules of thumb, including anchoring (adjusting upward or downward from a possibly irrelevant starting point), availability (conflating likelihood with ease of recall), and representativeness (conflating likelihood with similarity). In addition, we often show unrealistic optimism, we experience loss aversion (feeling losses harder than gains), we tend to stick to the status quo (including "default" options), and we are influenced by the framing of a decision.

- When our senses are stimulated or we are emotionally aroused, it becomes easier to succumb to the temptations of delicious food, a shopping spree, unprotected sex, smoking, alcohol, or simple laziness, even though we would otherwise prefer to avoid these. Furthermore, we often operate on a kind of mindless "autopilot" mode, eating whatever is in front of us. Many people do try to control their spending using a strategy called mental accounting (putting money in different jars or envelopes), even though this ignores the fungibility of money.

- Humans are social animals, so we tend to learn from others and seek their favor. We conform to the unanimous judgments and actions of the group, even when we privately disagree. We experience the spotlight effect, whereby we feel like people are paying more attention to us than they actually are. We are influenced in many subtle ways: we eat more when having dinner with others than alone; we are more likely to steal petrified wood from a national park when a sign says that many previous visitors have removed samples, and so on. When we are asked what we intend to do, we are more likely to do it (the mere-measurement effect, a kind of priming).

But how exactly do you go about designing a nudge? Thaler and Sunstein offer a handy acronym in Chapter 5:

- iNcentives -- In most cases, people notice when the price of something goes up, and they will demand less of it as a result. But opportunity costs are often less salient, so choice architects should consider whether and how to direct people's attention to incentives (for instance, making thermostats that tell consumers how much they can save on their energy bills).

- Understand mappings -- Here, the authors mean the relation between a choice and welfare. The idea is to make it easier to compare options, for example by translating information into an intuitive form. For insurance policies, credit cards, cell phone plans and so on, the authors suggest requiring price and usage disclosures from companies in the form of RECAP: record, evaluate, and compare alternative prices.

- Defaults -- People tend to take the path of least resistance and say "yeah, whatever". Thus, default options can be a powerful way to nudge people into a sensible choice. In some cases, especially simple yes-or-no decisions and emotionally charged issues, we might require people to actively choose an option.

- Give feedback -- Think about warning systems, or the way that digital cameras provide a fake shutter sound to let users know that a picture has been taken. The authors assert that feedback is the "best way to help Humans improve their performance" (p. 99).

- Expect error -- Of course, people will still make mistakes, and a well-designed system tolerates such errors. For example, your car might warn you if you are about to run out of gas, or make it impossible to leave the cap of the gas tank behind. This reminds me of the Heath brothers' maxim "prepare to be wrong".

- Structure complex choices -- When there are many options to choose from, consumers might need a simplifying strategy, like allowing them to "filter" alternatives by aspect or view recommendations based on the preferences of similar others.

|

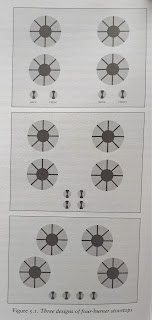

| The authors credit Norman's The Design of Everyday Things |

The rest of the book is primarily a collection of case studies of choice architecture in action. I'll outline them only briefly.

***

Improving decisions about health...

Jumping ahead to Chapter 10, we get acquainted with the American healthcare system, which requires people to have insurance to pay for prescription medication. When Nudge was written in 2008, Bush's Part D Medicare reforms offered senior citizens a huge selection of complex plans to choose from -- without much guidance to help them choose. The result was that a lot of people did not enroll, and those who did often had their default option chosen for them at random! To make matters worse, frequent changes in dug prices meant that the best option for you today might not be the best option tomorrow. Thaler and Sunstein recommend some improvements: (i) use "intelligent assignment" based on past prescription use instead of random assignment; and (ii) apply RECAP by reporting the costs of one's current plan and potential savings from switching to a comparable plan.Perhaps more exciting than Medicare is the issue of organ donations. To increase the supply of available organs, an obvious solution (from an economist's point of view) would be to legalize the market for organs. A more politically palatable solution might be to nudge people into becoming organ donors, by making use of the default effect. Most people support transplantation, but may be deterred from giving explicit consent (due to inertia). Thus, higher donor rates can be achieved by presuming consent, and giving people the ability to opt out if they wish. However, the authors suggest that because of the sensitive nature of the matter, mandated choice (e.g. you can't get your driving license unless you tick one of two boxes) may be even better.

A couple of extra nudges are tucked away in Chapter 14, which is titled "A Dozen Nudges" and, as you might be able to guess, describes twelve miscellaneous nudges. The health-related ones include an anti-smoking tactic, which entails a savings account that you can only reclaim if you pass a urine test showing that you haven't recently smoked; otherwise the money is donated to charity. On the topic of motorcycle helmets, a libertarian paternalist approach might be to let people ride without a helmet but only after obtaining a special license. To avoid large medical bills, a health insurance plan could encourage participants to work out at a health club or do a blood-pressure check in exchange for "Vitality Bucks" (which can be redeemed for hotel rooms, magazines, airline miles and so on). Teenage pregnancy can be discouraged by paying teen moms a dollar for each day that they're not pregnant. Finally, the chemical disulfiram can be added to nail polish to stop a nail-biting habit.

... Wealth...

Back in Chapter 6, Nudge discusses the research conducted by Richard Thaler in collaboration with Shlomo Benartzi on the "Save More Tomorrow" program. Basically, the idea was that people do not save enough for retirement (and admit it), so there should be a way to nudge people into joining a pension plan. One approach is automatic enrollment: these default plans often have savings rates of 2 to 3 percent, which may still be too low. By contrast, Save More Tomorrow asks participants to commit to increasing their contributions whenever they get a pay raise. This approach works, since people join with a low savings rate, increase it over time, and rarely ask to lower it back.Continuing the theme, Chapter 7 tackles the issue of choosing the right investment portfolio. Humans are notoriously bad at this, since we are influenced by emotions whenever stock prices fluctuate, such that we buy when prices are high and sell when they are low (the opposite of smart timing). People use simple heuristics, like investing in a 50-50 split between bonds and equities (and then forget to periodically rebalance their portfolio). The authors call this "naïve diversification". We might assist people through better choice architecture, along the lines of NUDGES: avoid conflicts of interest between employers and employees; show people what kinds of houses they would be able to afford at different levels of retirement income; choose a default option based on the participant's expected retirement date (called a target maturity fund); encourage automatic enrollment combined with Save More Tomorrow; and tailor the choice structure according to the participant's level of interest and sophistication (e.g. small versus full menus of mutual funds).

When talking about savings, we should also talk about debt: mortgages and credit cards can cause great hardship for people if they make poor decisions. Choosing a mortgage in the U.S. is hard because there are fixed-rate and variable-rate loans, interest-only loans, prepayment penalties, brokerage fees and so on. Predatory brokers can exploit unsophisticated borrowers. The nudge remedy is -- you may start to see a pattern by now -- to implement RECAP by requiring mortgage lenders to report fees, interest, caps on variable-rate changes and so on, so that borrowers or third-party services can more easily do comparison shopping. Likewise for credit cards, RECAP reports would make the costs of using credit cards more salient. Additionally, the authors assert that credit card companies should allow consumers to set up automatic payments of the monthly bill.

Next, the work of Richard Thaler and Henrik Cronqvist on the partial privatization of Social Security in Sweden is discussed in Chapter 9. In the early 2000s, Sweden implemented a pro-choice policy that gave working people the freedom to select up to five funds from a pool of hundreds of competing funds that were allowed to advertise. There was also a default fund, although the Swedish government discouraged its selection. Cronqvist and Thaler found that among those who selected their own portfolios, a greater share went to Swedish equities, and less went to foreign equities, index funds or fixed-income securities (e.g. bonds). Thus, the actively-chosen portfolios on average performed worse than the default one. The advertising didn't help: it lured people into riskier funds with higher fees. The authors conclude that "Just Maximize Choices" probably wasn't the right mantra. It would have been better if the Swedish government did not discourage the default.

Some more money-related nudges, mentioned in Chapter 14, include automatic tax returns (which are already used in some countries, but not the USA), red lights that remind people to replace their air conditioner filters, and gambling self-bans. The simple idea of the latter is to put oneself on a list so that casinos will refuse entry -- a handy way to resist addiction. Speaking of casinos... The Postscript of Nudge (added in the revised edition) talks about the 2008 financial crisis, and offers an explanation in terms of the human frailties of bounded rationality, limited self-control and social influences. The complexity of financial products, the temptation to refinance mortgages, and the "social contagion" surrounding real estate prices, all contributed to the crisis. (For another behavioral interpretation, see Akerlof and Shiller's book.) Unsurprisingly, Thaler and Sunstein recommend the application of RECAP, but they also have other ideas: nudge people toward paying off their loans rather than refinancing, and create default provisions.

... and Happiness

Like (partially) privatizing Social Security, governments may also consider privatizing marriage. Chapter 13 of Nudge proposes a radical plan to remove the word "marriage" from all laws, in the name of libertarian paternalism. The aim is to give religious organizations the freedom not to recognize same-sex marriage (or marriages from other churches), while preserving the freedom of individuals to make commitments to each other. Thaler and Sunstein suggest that governments deal with civil unions (available to same-sex and opposite-sex couples) that provide material benefits like tax benefits, ownership and inheritance benefits, and so on, while leaving the symbolic and expressive benefits of "marriage" to the private sphere. They argue that official marriage licenses are obsolete; but there is still a role for choice architecture in setting default rules for divorces.What better way to improve your happiness than to help others? Chapter 14 proposes a "Give More Tomorrow" program, based on Save More Tomorrow but with charitable donations instead of savings. A related idea would be a so-called "Charity Debit Card" that keeps track of all your donations, perhaps automatically sending a statement to the tax authorities for tax deductions. (Even better, I think, would be if it nudged one towards effective charities.) For other kinds of commitments, such as improving one's grades or traveling to Mongolia, apps like Stickk.com can help people stick to those commitments, by including (mild) penalties for failure. Thaler and Sunstein even propose a "Civility Check" software that warns you when you're about to send an angry email!

I left Chapter 12 for last, as it is a bit hard to place -- the issues of environmental pollution, biodiversity loss, ozone depletion, and climate change are in some ways related to health, wealth, and happiness. Thaler and Sunstein come out against heavy command-and-control regulations, because of course, such laws are not libertarian. They prefer nudges that (a) align people's incentives with environmentally-friendly choices; and (b) give people feedback on the environmental impacts of their actions. For example, a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system can improve incentives (The Undercover Economist would agree), while required disclosures can inform and motivate consumers to avoid a company's products. Governments can also nudge companies through programs that offer positive publicity and other awards for improving energy efficiency.

***

Kudos to Thaler and Sunstein for dedicating a whole chapter (Chapter 15) to criticisms of their approach. They address the following points:

- Won't libertarian paternalism lead us down a slippery slope to coercive bans? The authors argue that this is a separate issue from whether their proposals have merit in and of themselves. Moreover, the steepness of the slope is reduced by the "libertarian" aspect of libertarian paternalism, which may in some cases increase freedom relative to the status quo. Finally, they reiterate that some kind of choice architecture is inevitable, and that government cannot simply be absent.

- What if choice architects nudge with their own venal interests in mind? The response from Thaler and Sunstein is that there are legitimate concerns around conflicts of interest, but that these can be addressed through rules about competition, transparency and labeling, and it doesn't mean that we need to stop with architecture.

- Shouldn't we grant people the right to be wrong? Don't people learn by making mistakes? Well, the authors agree, which is why they insist on opt-out rights. But as they put it: "We do not believe that children should learn the dangers of swimming pools by falling in and hoping for the best. Should pedestrians in London get hit by a double-decker bus to teach them to 'look right'? Isn't a reminder on the sidewalk better?" (p. 241).

- Doesn't libertarianism favor active choosing as opposed to nudges? And what about redistribution? As the golden rule says, a nudge should not impose (high) costs on those who do not need help -- and most nudges don't, but in some cases (e.g. healthcare) it might be worth it to ask everyone to share the cost of helping the worst-off members of society, because it also benefits everyone. As for active choosing: it's fine when choices are easy, but in other cases it may not be wise (or libertarian) to compel people to make choices.

- Aren't nudges kind of like subliminal advertising? Not really: the authors endorse John Rawls's publicity principle, which states that the government shouldn't enact a policy that it would not be able or willing to defend publicly.

- Shouldn't the government be neutral regarding people's choices? In the case of religion or voting, yes. But if an outside expert can help someone with a difficult choice (e.g. selecting a mortgage), without much risk of corruption, it's a different matter.

- Why stop at libertarian paternalism? Can't we improve people's lives through mandates and bans? Again, Thaler and Sunstein argue that we need to do a cost-benefit analysis, weighing up the benefits that regulation may bring to the least sophisticated people against the costs imposed on the most sophisticated ones. For example, it might be sensible to require a "cooling-off period" before a couple can get divorced, but more intrusive mandates are more likely to lead down a slippery slope.

"The sheer complexity of modern life, and the astounding pace of technological and global change, undermine arguments for rigid mandates or for dogmatic laissez-faire." (p. 254)

So there you have it.

***

My overall impression of Nudge is fairly positive, and there is a lot to like about this book. Thaler and Sunstein make a clear and straightforward case for (i) what a libertarian-paternalist nudge is; (ii) when such nudges are most likely to be useful; and (iii) what kinds of methods choice architects can use. They give plenty of examples, some of which take the form of detailed, in-depth case studies of real policies. They base their work on a lot of research, and make room to consider objections to their claims. The reader may even detect a bit of humor sprinkled here and there (at some point, the authors even quote a scene from The Simpsons). So, on paper, the book ticks all the boxes.

The main reasons I hesitate to give it a full five stars are firstly that some of the more detailed policy descriptions in chapters 6-12 can be a bit tedious to read, and secondly that the idea of using behavioral science to influence people's behavior isn't wholly original. On the first point, I suppose that the reader can simply skip those less interesting parts. But the authors could have helped by being less repetitive and discussing relevant topics that they left out, such as assimilation and contrast effects, primacy and recency effects, etc. On the second point, the predecessor to Nudge is arguably Robert Cialdini's famous Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, originally published in 1984 (over two decades before Nudge!). Cialdini provides numerous examples of how people are influenced by social conformity, consistency (a kind of inertia), and heuristics (like placing a higher value on supposedly scarce things, listening to authority figures, returning favors and so on). Some of the compliance techniques, such as the "foot-in-the-door" or "low-ball" techniques, are even reminiscent of the escalating commitment of Thaler and Benartzi's Save More Tomorrow program! Of course, what makes Nudge different is that its focus is on policies that help people and are publicly defensible (as per the golden rule and the publicity principle), whereas car salesmen typically won't tell you that they intend to low-ball you.

Nonetheless, Thaler and Sunstein deserve credit for bringing this body of knowledge into public policy. Their book has probably motivated the testing of many nudge interventions, and therefore indirectly the replication (or lack thereof) of behavioral science predictions. It has also spurred discussion about the limitations of choice architecture; one question, for instance, is whether nudging can lead to long-term behavior change -- perhaps a better understanding of habits can help in this regard. Choice architecture seems to be just one piece in the overall puzzle.

Perhaps another limitation is that libertarian paternalism works mostly for choices where there is little impact on nonconsenting parties. In other words, it could be used to support the decriminalization of "victimless crimes", but for other crimes a nudge may not be sufficient. This relates to a point of contention that I suspect some folks (especially on the Left) might have: while it's one thing to let individuals make bad choices if they really want to, it's another thing to let unscrupulous companies promote such choices.

According to some reviews, Nudge is supposed to change the way one thinks about the world. I think that's true to some extent, in the sense that the reader will be more likely to "pull policy ropes sideways", in the terminology of Robin Hanson. But is it as sweeping as Antifragile, as informative as Factfulness, as grand as Life 3.0, or as captivating as Sapiens? I don't know; probably not. That being said, this book is still required reading for those interested in behavioral economics.

The main reasons I hesitate to give it a full five stars are firstly that some of the more detailed policy descriptions in chapters 6-12 can be a bit tedious to read, and secondly that the idea of using behavioral science to influence people's behavior isn't wholly original. On the first point, I suppose that the reader can simply skip those less interesting parts. But the authors could have helped by being less repetitive and discussing relevant topics that they left out, such as assimilation and contrast effects, primacy and recency effects, etc. On the second point, the predecessor to Nudge is arguably Robert Cialdini's famous Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, originally published in 1984 (over two decades before Nudge!). Cialdini provides numerous examples of how people are influenced by social conformity, consistency (a kind of inertia), and heuristics (like placing a higher value on supposedly scarce things, listening to authority figures, returning favors and so on). Some of the compliance techniques, such as the "foot-in-the-door" or "low-ball" techniques, are even reminiscent of the escalating commitment of Thaler and Benartzi's Save More Tomorrow program! Of course, what makes Nudge different is that its focus is on policies that help people and are publicly defensible (as per the golden rule and the publicity principle), whereas car salesmen typically won't tell you that they intend to low-ball you.

Nonetheless, Thaler and Sunstein deserve credit for bringing this body of knowledge into public policy. Their book has probably motivated the testing of many nudge interventions, and therefore indirectly the replication (or lack thereof) of behavioral science predictions. It has also spurred discussion about the limitations of choice architecture; one question, for instance, is whether nudging can lead to long-term behavior change -- perhaps a better understanding of habits can help in this regard. Choice architecture seems to be just one piece in the overall puzzle.

Perhaps another limitation is that libertarian paternalism works mostly for choices where there is little impact on nonconsenting parties. In other words, it could be used to support the decriminalization of "victimless crimes", but for other crimes a nudge may not be sufficient. This relates to a point of contention that I suspect some folks (especially on the Left) might have: while it's one thing to let individuals make bad choices if they really want to, it's another thing to let unscrupulous companies promote such choices.

According to some reviews, Nudge is supposed to change the way one thinks about the world. I think that's true to some extent, in the sense that the reader will be more likely to "pull policy ropes sideways", in the terminology of Robin Hanson. But is it as sweeping as Antifragile, as informative as Factfulness, as grand as Life 3.0, or as captivating as Sapiens? I don't know; probably not. That being said, this book is still required reading for those interested in behavioral economics.

Comments

Post a Comment